Description

NAOE SHIZU

Aside from Sadamune, I believe Shizu, Samonji, and this Go [Yoshihiro] should form the top three among the ten [of Masamune’s disciples]. — Dr. Honma Junji

Shizu Saburo Kaneuji is a grand master swordsmith working from the end of the Kamakura period into the beginning of the Nanbokucho period. He was highly influential, and is the founder of the Mino tradition – one of the five general koto styles of swordsmithing. His path through life lead him from his beginnings in Yamato as a Tegai smith most likely working under Kanenaga, to tutelage under Masamune in Kamakura around 1319. He finally settled in the Shizu area of Mino province at the beginning of the Nanbokucho period. The mastery of the Soshu and Yamato traditions merged in his teachings to become the Mino tradition.

Kaneuji started by signing his name with these characters: 包氏. The first character, for Kane, is commonly found in Yamato smiths and was handed down through the students he left behind when he moved to Kamakura. On his arrival to be taught by Masamune, he changed his signature to 兼氏 which was still read as Kaneuji. He has work signed like this that still is in Yamato tradition, showing that he may have come to produce in Kamakura and then learned from Masamune as a secondary effect of being fellow residents. After Kamakura, he moved to Shizu in Mino province, and he is now generally referred to with the nickname Shizu as a result of his final place of work.

Swords from his time period in Yamato are referred to as Yamato Shizu because of the nickname we use for him today. His work after his learning with Masamune are simply referred to as Shizu. This however makes for some points of confusion, because the students he left behind in Yamato are also collectively referred to as Yamato Shizu and there was also a nidai Kaneuji who left behind some excellent works in Yamato. Context is then necessary whenever examining a blade attributed to Yamato Shizu to determine if it is a school or individual attribution.

The students Shizu Kaneuji left behind in Mino when he died are called Naoe Shizu, as they moved and settled in Naoe which was a village in the northern part of Shizu. These Naoe Shizu smiths are known individually as Kanetsugu, Kanenobu, Kanetomo, and Kanetoshi and may also have been sons of his. Since they typically made Nanbokucho style sugata that have been cut down with signatures lost, they were particularly subject to losing their signatures. Today, there are no signed tachi left by the Naoe Shizu group. This leads to the frequent use of the school classification when attributing to them, but we know the work styles and the smiths by signed tanto and ko-wakizashi.

Kaneuji is famous today for being the student of Masamune who’s work was closest in style to the master. We can confirm through dated works that were recorded in the Edo period that his dates align with the historical production of Masamune. Masamune of course is hailed as the greatest of the Soshu smiths and is usually considered the greatest smith of all time.

Of the Naoe Shizu smiths, there is a nidai Kaneuji, and a sandai Kaneuji. The smith Kanetsugu among the Naoe Shizu smiths is said to be the son of Kaneuji, and it is possible that he is also the nidai Kaneuji. The style of the Naoe Shizu smiths is generally similar to Shizu but a level lower in quality, and those at the topmost level of quality may be thought to be works of Kaneuji now, it is difficult to tell in some cases.

The school smiths have very few signed blades compared with Shizu Saburo Kaneuji. Today, there is no tachi known with this signature, and only wakizashi and tanto are seen with this signature. Kanetsugu has one Juyo Bijutsuhin tanto beside this one, and Kanenobu has two Juyo Token tanto. Generally, no later than the Nanbokucho time, Kaneuji hamon mostly have a large pattern, and sometimes ko-gunome styles are seen. With either style, one does not see a whitish jihada, and there are strong nie on the ji and ha.

Kanetsugu, Kanetomo, and Kanenobu’s Naoe Shizu smiths hamon have smaller patterns and a somewhat whitish jihada when compared to Kaneuji’s work, but Kanetsugu’s work shows swords with both styles: a whitish jihada and with no whitish jihada. This wakizashi [by Naoe Shizu Kanetsugu] is a large size with somewhat large pattern gunome, and the jihada is not whitish. The ji and ha are clear, the glamorous boshi is a midare hamon and appears like a like a flame, and blade is full of spirit, and this is the O-Shizu style, and this is valuable information showing us that already in Kanno times (1350), this kind of shape has appeared. — NBTHK Token Bijutsu

Today Shizu’s swords rank from Juyo (of which he has 130, placing #6 overall in the list of makers) and Tokubetsu Juyo (of which he has 14). He also has works ranked Juyo Bijutsuhin and Juyo Bunkazai. He is of course regarded by Fujishiro as Sai-jo Saku, the rating of a grandmaster swordsmith.

The Naoe Shizu works that have been ranked at Juyo by the NBTHK number 157. Of these only 7 are signed, which illustrates one of the problems left to us in differentiating the Naoe Shizu smiths. On top of the Juyo there are another four Juyo Bijutsuhin, with two by Kanetomo, one by Kanetsugu, and one unsigned and attributed to the school.

Tokubetsu Hozon

Naoe Shizu Tanto

This is a great example of Soshu work from the middle Nanbokucho period. This tanto is a bit polished down but still retains an extremely impressive hamon. This blade is very similar in structure to the IMAGAWA SHIZU that I had on my site previously, where the hamon is the type that Kiyomaro copied and in fact is a lot closer to Shizu Kaneuji than to what is traditionally considered to be Naoe Shizu. Naoe Shizu works tend to have a lot less activity than what we see here, with very strong kinsuji and lots of

sunagashi as well as dramatic ups and downs in the hamon.

The horimono on this blade is a gomabashi on one side which reflects chopsticks used in Buddhist ritual and invokes Kannon (Kanzeon Bosatsu), the goddess of mercy. On the opposite is a suken with tsume. The suken is an attribute of Fudo Myoo, the god of justice. This horimono layout is found on the works of various Soshu smiths starting with Soshu Sadamune.

Together these represent the opposites of forgiveness/atonement and

punishment/justice, which reflect back on sayings about the sword that gives life, and the sword that takes life. The exact meaning is left for you to ponder but invokes philosophical choices and about the application of power that the sword represents. In the balance of these two extremes, one can hope for enlightenment and to use the sword or one’s power in life in the appropriate manner at the appropriate time. Such a message would be left to the owner to consider, and reconsider as he wore, wielded and cared for his blade and a constant reminder of his duty and responsibility.

Shizu himself did not leave very many signed tanto behind but one of the very best examples has extremely similar hamon to this blade. There are according to the NBTHK just two authentic signed Kaneuji tanto. This blade shown here has a similar shape to the signed blade as well. Both have some muneyaki and intense sunagashi as well as a hamon that moves up past the midpoint of the ji and back down to close to the ha. The signed one though is quite small at only 19.15 cm and in spite of that small size someone cut off the end of the nakago jiri. Probably the machi was moved up a bit in that tanto too when this was done and it started out around 22-23 cm. For some reason these smiths that made large blades in the Nanbokucho period like Chogi and Shizu, along with Samonji made tanto that were quite small and we’re not so sure why. It is possibly for convenience as a weapon of last resort when carrying an oversized tachi. Though this signed Kaneuji is not papered, the NBTHK documented it in the Token Bijutsu as one of the 12 annual masterpiece works for education and the signature is not in doubt.

This blade was made unsigned and is ubu, but the condition of the end of the nakago jiri being kengyo is consistent with an older attribution to Soshu Sadamune. The blade does have a sayagaki on it which is unsigned attributing it to Takagi Sadamune. Takagi Sadamune was either the second generation Soshu Sadamune or else his son, as there are many stories of Sadamune moving to Goshu (Takagi) at the end of his career. Old oshigata books have many clean examples of this Takagi Sadamune mei but only one blade has survived to the present day. The sayagaki also values the blade very highly at 200 gold coins. Given the nakago, an attribution to Takagi Sadamune or Soshu Sadamune is not out of the question, but Takagi Sadamune’s work tends to be a bit bigger and the hamon is more in keeping with Shizu Kaneuji.

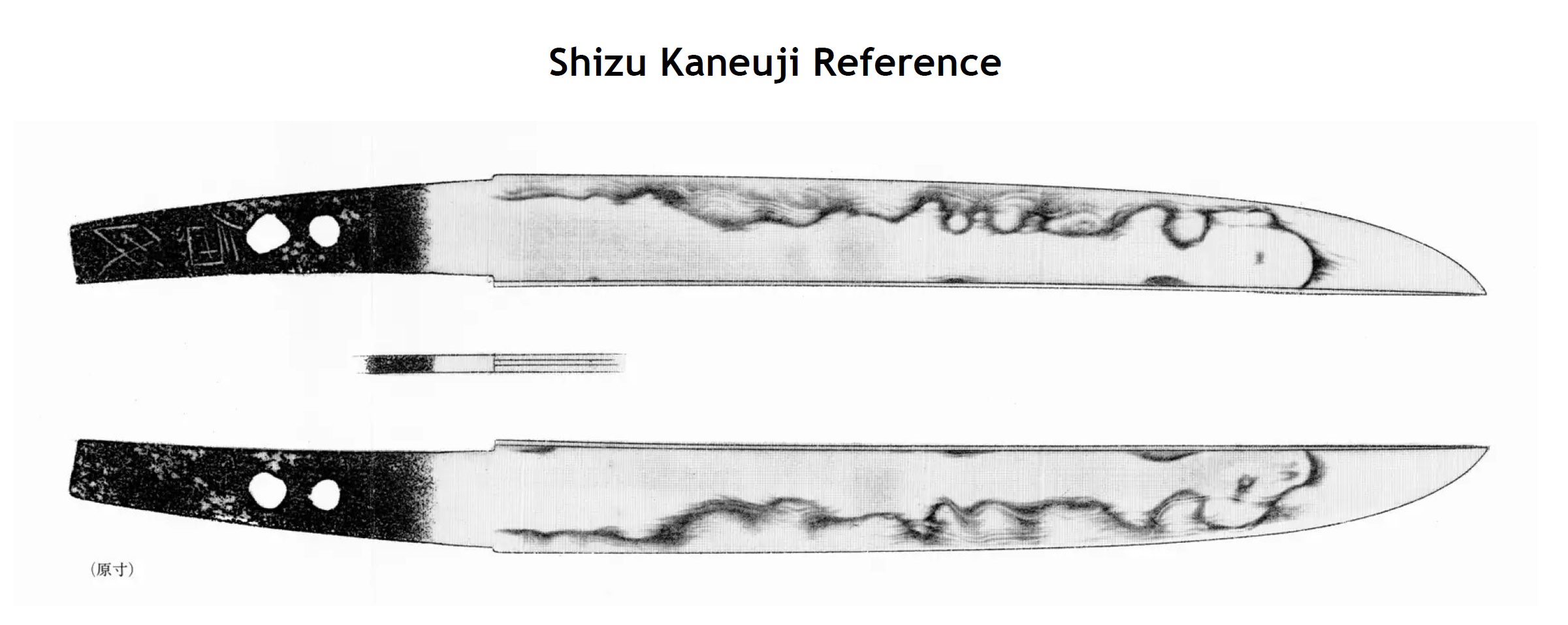

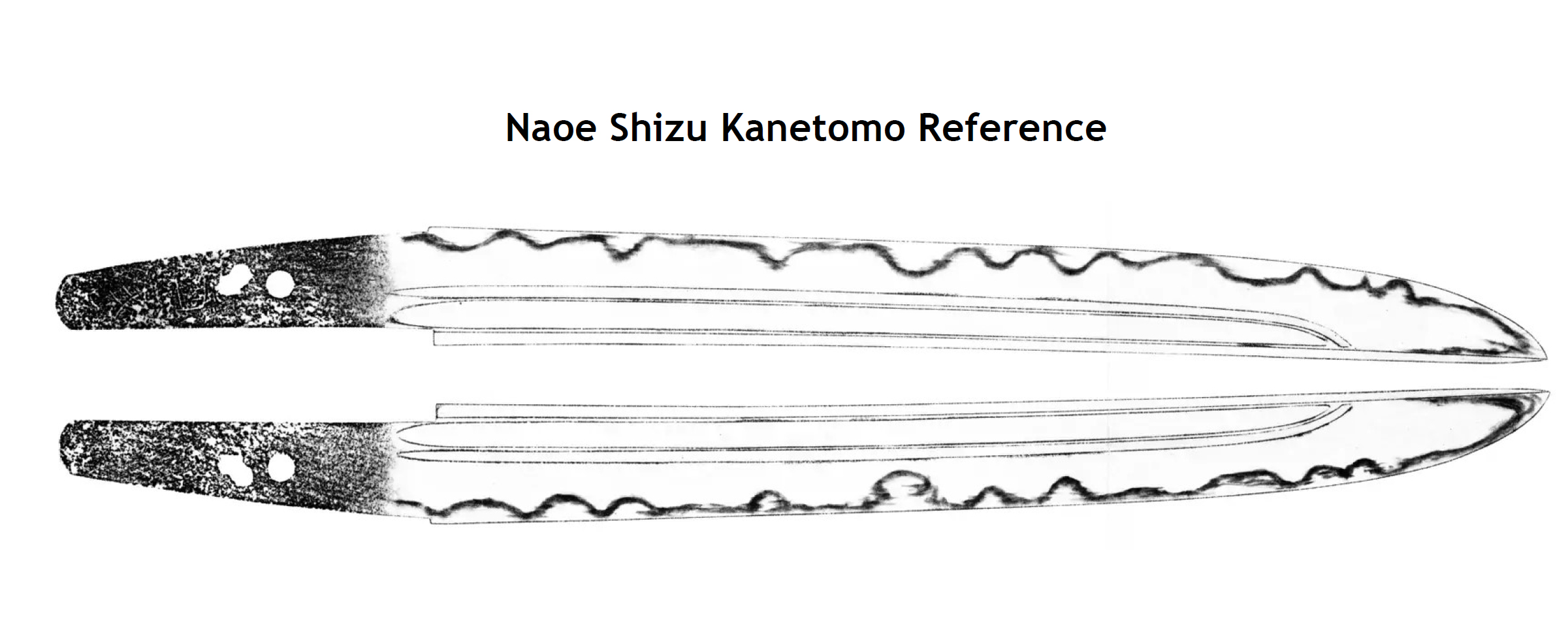

The Imagawa Shizu which had this same structure had some contesting opinions about it being Shizu or Naoe Shizu, and in this case as Tanobe sensei would say “Naoe Shizu is safe harbor” meaning that it is a conservative call. I personally think that these very vivid works are more likely to be Kaneuji than they are to be his students. Especially in this case with the signed reference piece having such a strong resemblance in the hamon, it makes a strong argument. I put up the Kaneuji reference as well as a signed example of one of his students, Kanetomo, which is very typical for the Naoe Shizu school. In case you want to check my text, you can do so very easily with your eyes and judge which you think matches this work best. The Kanetomo in this case is Juyo Bijutsuhin and is itself a masterpiece. Even so the activity is not as intense as Shizu Kaneuji.

This tanto as mentioned is a bit polished down but I think has a case to be made for Juyo especially on the strength of the hamon. I have not yet brought it to Tanobe sensei for his opinion but I will likely do this in the future.

Regardless of the above, it is very hard to find any exciting Soshu blades in the current market. New collectors who come into this field as well as existing ones are very fond of Soshu work (as am I), because good works are always very exciting and dynamic. This tanto shows the best qualities of Soshu den particularly in Shizu style in the hamon. Shizu tanto are unusual to find and Naoe Shizu tanto while still quite unusual do not generally have this amount vivid nie in them. Because of this, this blade I think is a nice acquisition for anyone who wants a good Soshu example but cannot step into a Juyo work. And I think that there is potential for Juyo in the future but this needs a bit more background investigation about the attribution before it can get there.

This blade also has a nice Edo period koshirae featuring some very nice lacquer work and several family mon. Japanese ownership is notoriously flippant when it comes to keeping kozuka original so I think it is more likely that the original kozuka for this blade was kiri mon that matched the menuki but at this point it’s hard to tell. This kind of menuki would end up attributed to the Goto school or else Kyo Kinko or Yoshioka most of the time.

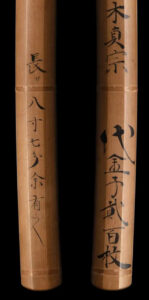

Tanto Sayagaki

This sayagaki is for the Naoe Shizu tanto and dates to the end of the Edo period but the author is unknown.

1. 高木貞宗

Takagi Sadamune

2. 代金子貮百枚

Dai kinsu nihyaku-mai Valued at 200 gold coins

3. 長サ八寸七分有之

Nagasa hachisun nanabu ari kore The length is 8 sun 7 bu (26.4 cm)