Description

Osafune Masamitsu

The Bizen tradition of sword making holds within it, the two most major schools; the Ichimonji and its several branches, and the Osafune. The numbers of excellent smiths this region and these schools produced is staggering, with tenure from the Heian era all the way to the 19th century. The Osafune schools accepted founding smith was Mitsutada. Mitsutada in turn rendered the “Sansaku” or three famous smiths of Osafune, Nagamitsu, Kagemitsu, and Sanenaga. Following in stride was the Shodai Kanemitsu, referred to as “O” or the “great” Kanemitsu that also is regarded as one of Masamune’s ten gifted pupils, or “Jutetsu”. By examining the time line extension and the evolution of works, Kanemitsu is thought to have a second generation of the same name that in turn produced this smith, Masamitsu, who worked from about the middle of the Nambokucho era into the beginning of Oei.

For anyone even vaguely familiar with Japanese swords, the mere mention of swords from the Nambokucho period will draw a mental image of shapes from bold to even greatly exaggerated proportions. The reality is that these exaggerated forms coexisted with more fundamental, yet mildly robust forms, and were the exception rather than the rule, but the impact of such large shapes anchors first impressions to a mental precedent. It was a confused period in Japanese political history with two courts ruling Japan divided by north and south, political bickering and battles skirmished between them, and the threat of the Mongols beyond the western horizon still loomed. The elegant sword shapes of the Kamakura period were expanded to bold, massive shapes that would presumably function as more durable and maintainable weapons under repeated battlefield conditions. The trade off by nature of this design was difficulty of handling and the ensuing fatigue of wielding such weapons over long periods, and also the larger amount of raw materials required to make them. The period was short, lasting only about 60 years, but the shapes from the period, and the respective quality they were necessarily forged, made a lasting impression on the craft. Smiths began to make copies inspired by these shapes in subsequent centuries, and contemporary smiths often make them to this day.

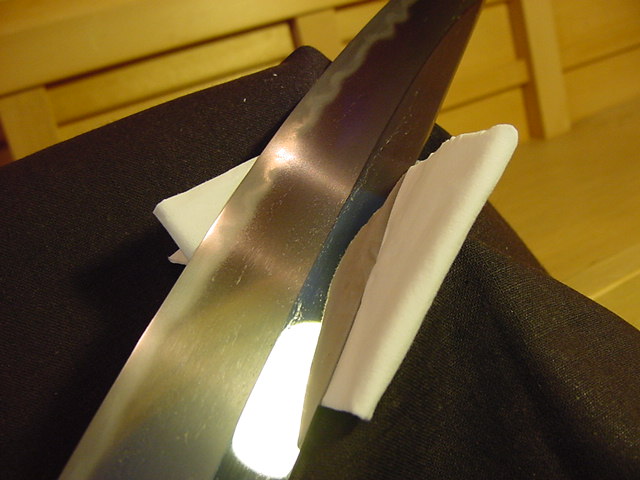

As warfare methods changed yet again, and sword shapes returned to those reminiscent of Kamakura era blades, the massive Nambokucho swords were shortened to accommodate new conditions of battle and methods of carrying. The big naginata were also greatly shortened at the nakago and additionally, the long sweeps of the tips removed to provide the easier draw of a katana style “bukezukuri” mounting worn with the cutting edges facing up, becoming “naoshi” or “corrected”. Removing so much of the tip altered not only the sori, but also resulted in the removal of any original boshi, leaving the yakiba falling directly off the mune in yakitsume style. The widened flare of the original kissakis niku was also lost to this alteration. This results in the very thin mune at the tip. The fact that such care was taken to extend the useful life of these swords tells the respect for the quality by which they were made. Yet again, the shape of this naginata-naoshi became a focal point for revival creations in the ensuing centuries also, influencing many new creations based upon this evolution.

Masamitsu worked circa 1356-1394 (Embun to Oei period), and was among several smiths of acclaim in his time. Although his contemporary, Rin Tomomitsu (rated Jojosaku), is generally regarded superior, Masamitsu’s 48 listed Juyo works illustrate his capacity for consistant quality.

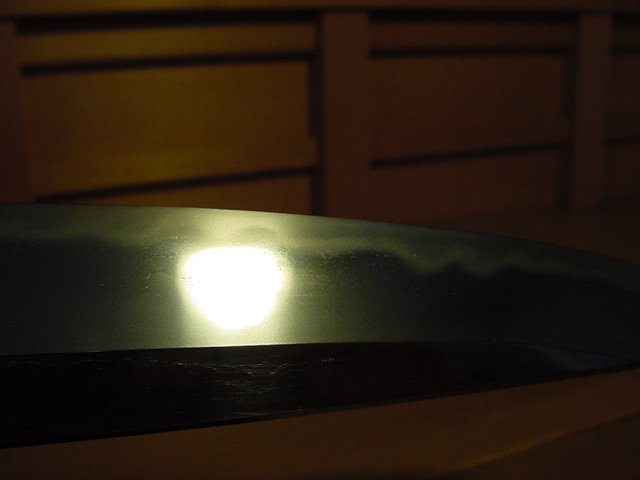

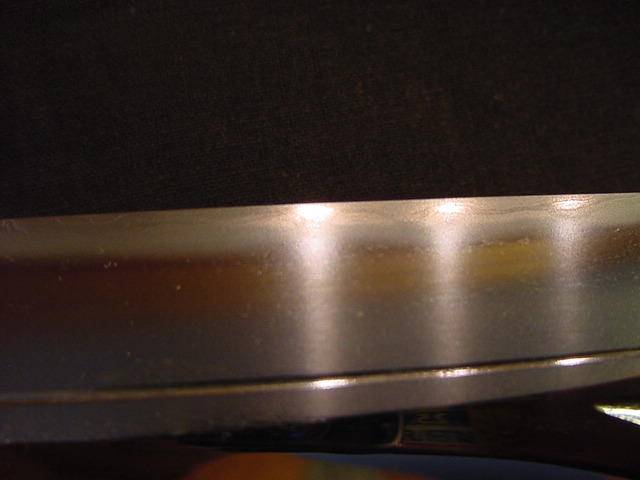

The work in this sword displays the clear influence of Kanemitsu in the slightly togare (pointed) sloped shoulder gunome, with wide valleys in between. Also the wide bo-utsuri with a narrow belt is seen in Kanemitsu works. There is some slight mistiness pulling off the tops of some gunome into the ji. There are hataraki inside the yakiba with many fine workings. The hada is a running itame with some mokume. The jigane displays some slight loosness in places, both a product of its age and the hada large naginata of this type exhibit many times. This is neither detrimental to the quality or condition of the steel that shows nice texture, color, and luster. There are several very small hakebori (chips) in the edge that speak of the sword’s history and durability. The decision to leave them by the polisher was wise to promote the life of the sword for future generations. Interestingly there is mitsumune extending from the munemachi, tapering away at the bevel in the shinogiji. It is unusual in Bizen, but does occur in Masamitsu’s recorded works, and perhaps another influence of Kanemitsu’s extended education in Soshu-den with Masamune. This sword has been greatly shortened from the nakago and the kissaki corrected as aforementioned, yet still retains an impressive 29 1/8 inches of length. There are many hours of enjoyment to be had studying every inch. The habaki is gold foiled.

This sword has been awarded Juyo level papers which attribute it directly to Masamitsu. There are many swords rated Juyo and above that are documented with the prefix character of “den” which means roughly “in the tradition of” that school or smith. This in itself is not a derogatory comment, but merely alludes that the sword has variance in the work that holds it just outside normal accepted character for that school or smith. It may either be the inclusion of some type of activity, or the lack of some form. In either case, the work must be examined on its own merits, and the direct attribution of the work to a maker without the addition of “den” provides a clear conclusion that this is unmistakable textbook work of that school or individual.

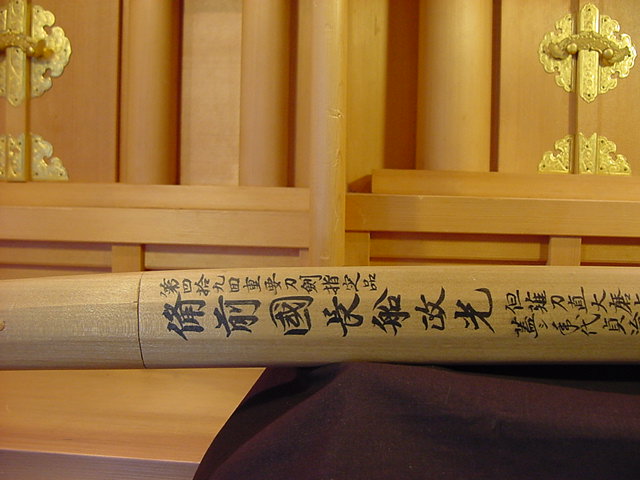

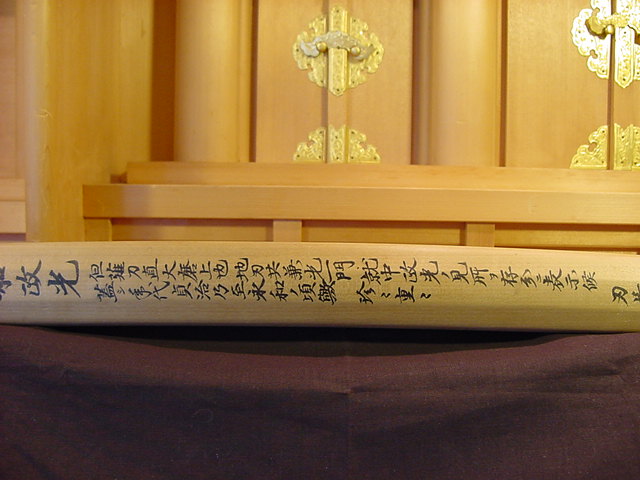

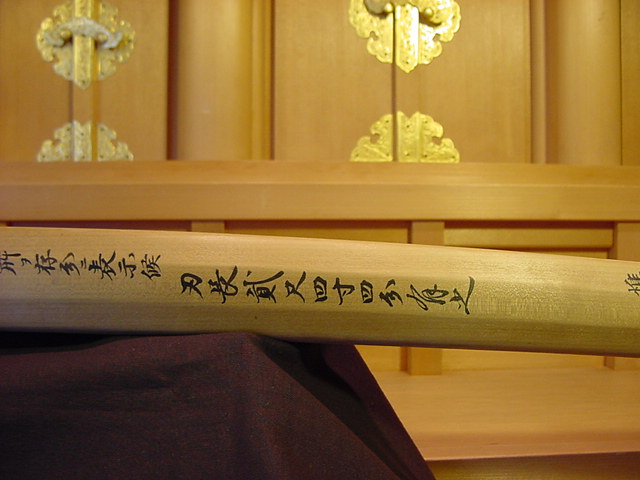

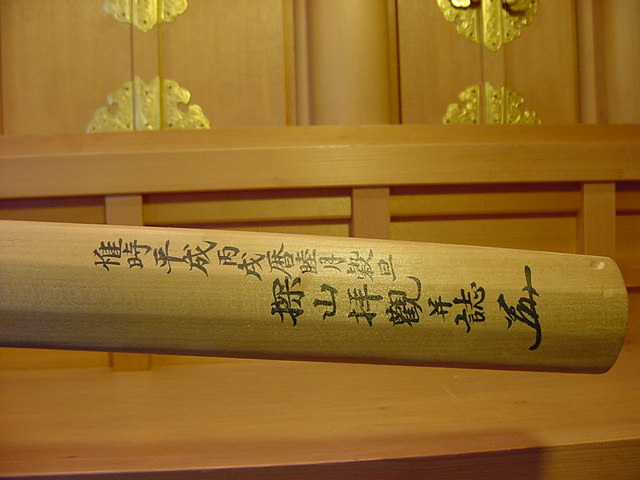

The sayagaki on this blade is by Mr. Michihiro Tanobe. Within the comments of the maker, length, time period, etc., he added the very complimentary “Chin Chin, Cho Cho” which is “rare and precious” each repeated for emphasis. My friend Andy told me of the time he spoke with Mr. Tanobe about this comment and its meaning. Mr. Tanobe replied simply that “If the house is burning down, and you can save only one sword, this is the sword you save”. It is interesting to note that the verb “chincho suru” means “to cherish as a rarity”. The eloquence of Mr. Tanobe’s description sums it all up.

.