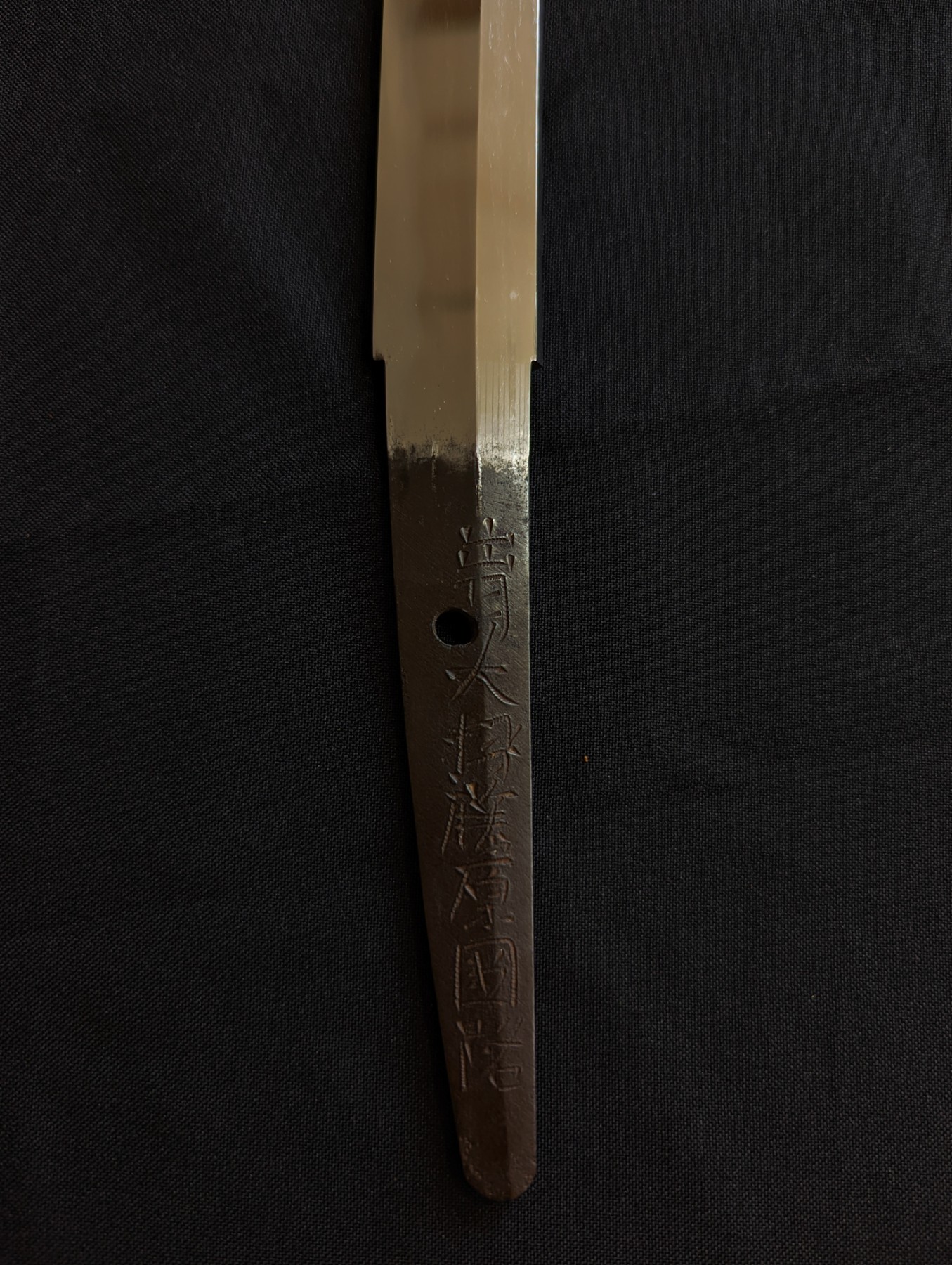

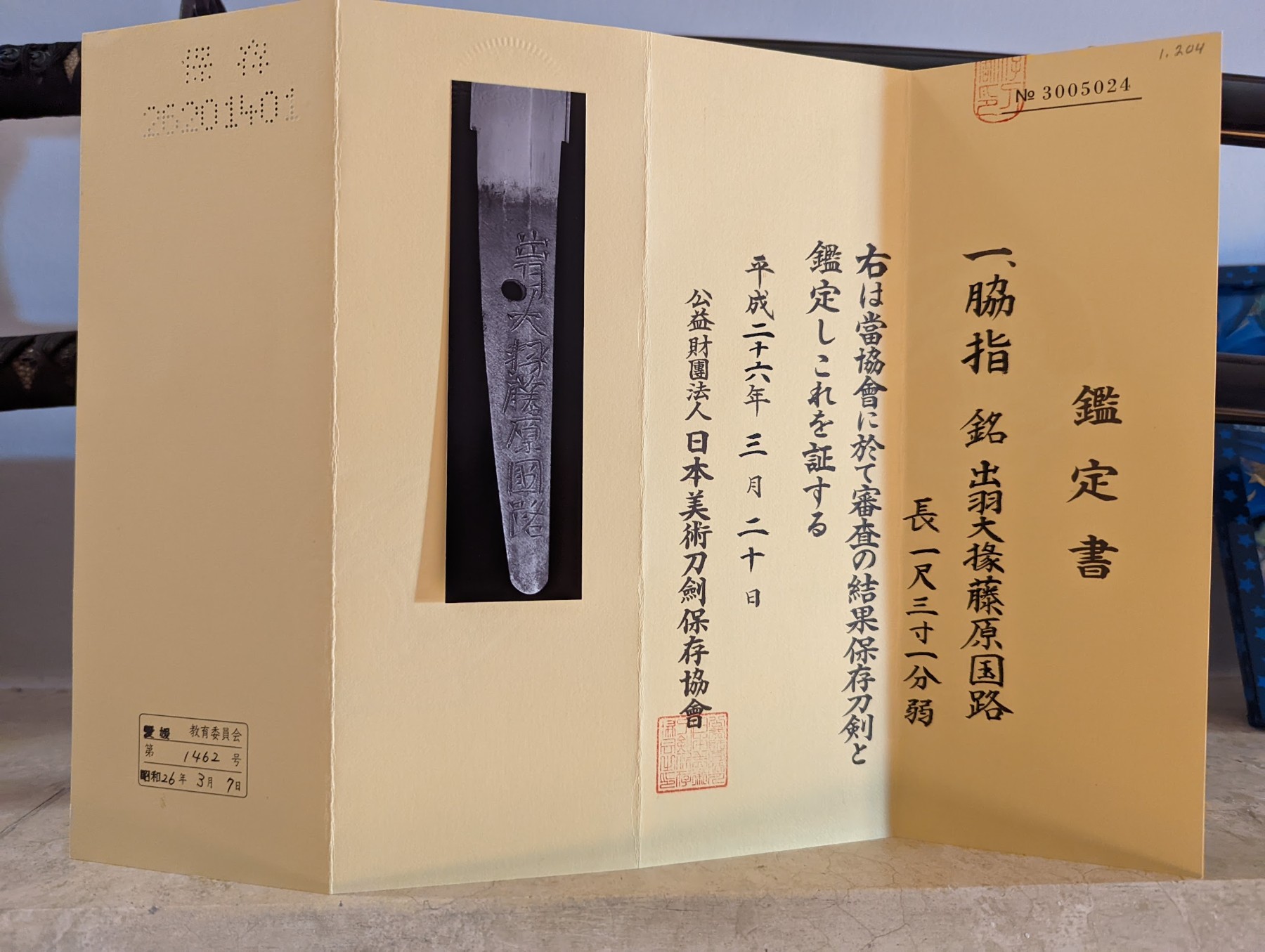

Wakizashi by the famous top student of Horikawa Kunihiro. Jojo-saku smith rated. Per the NBTHK:

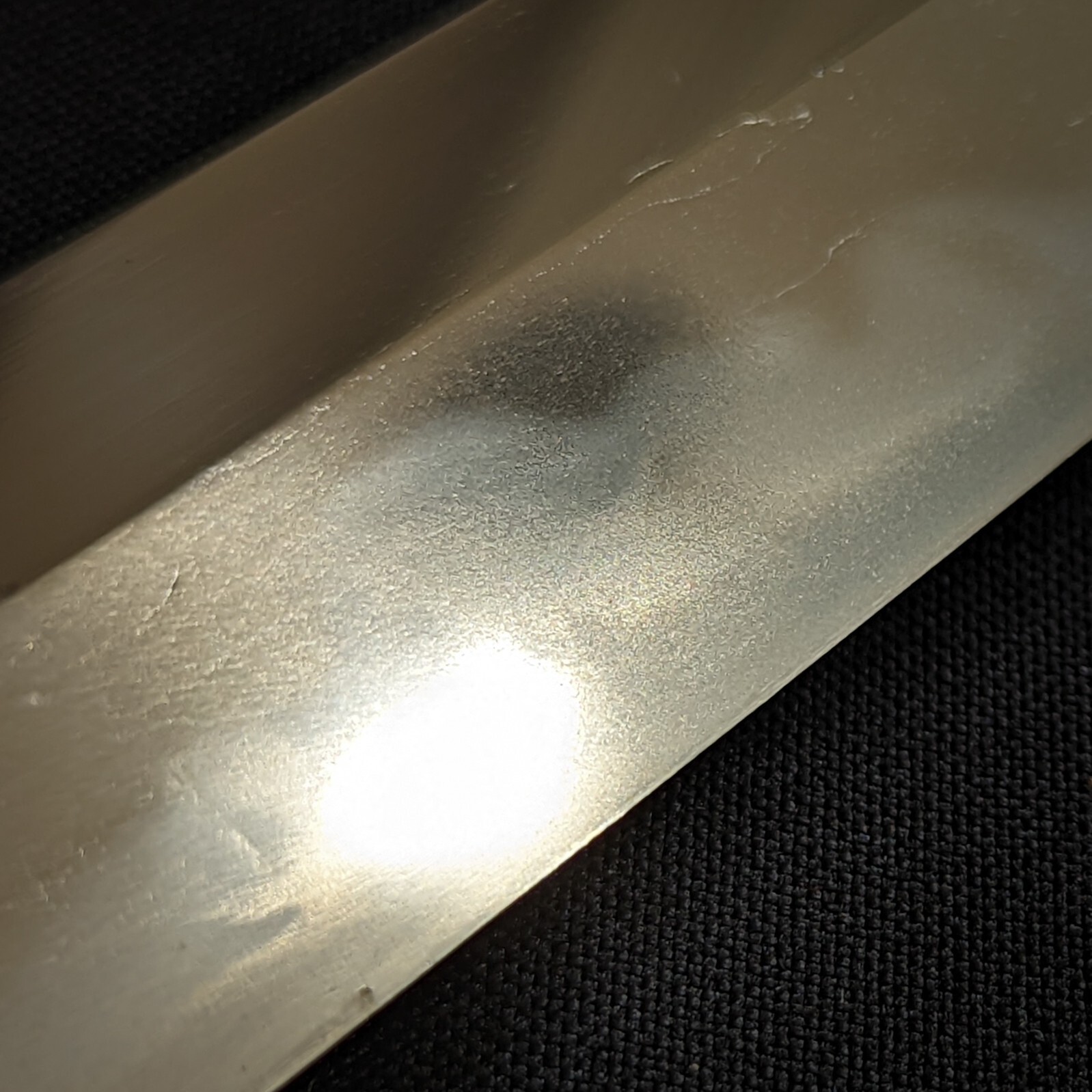

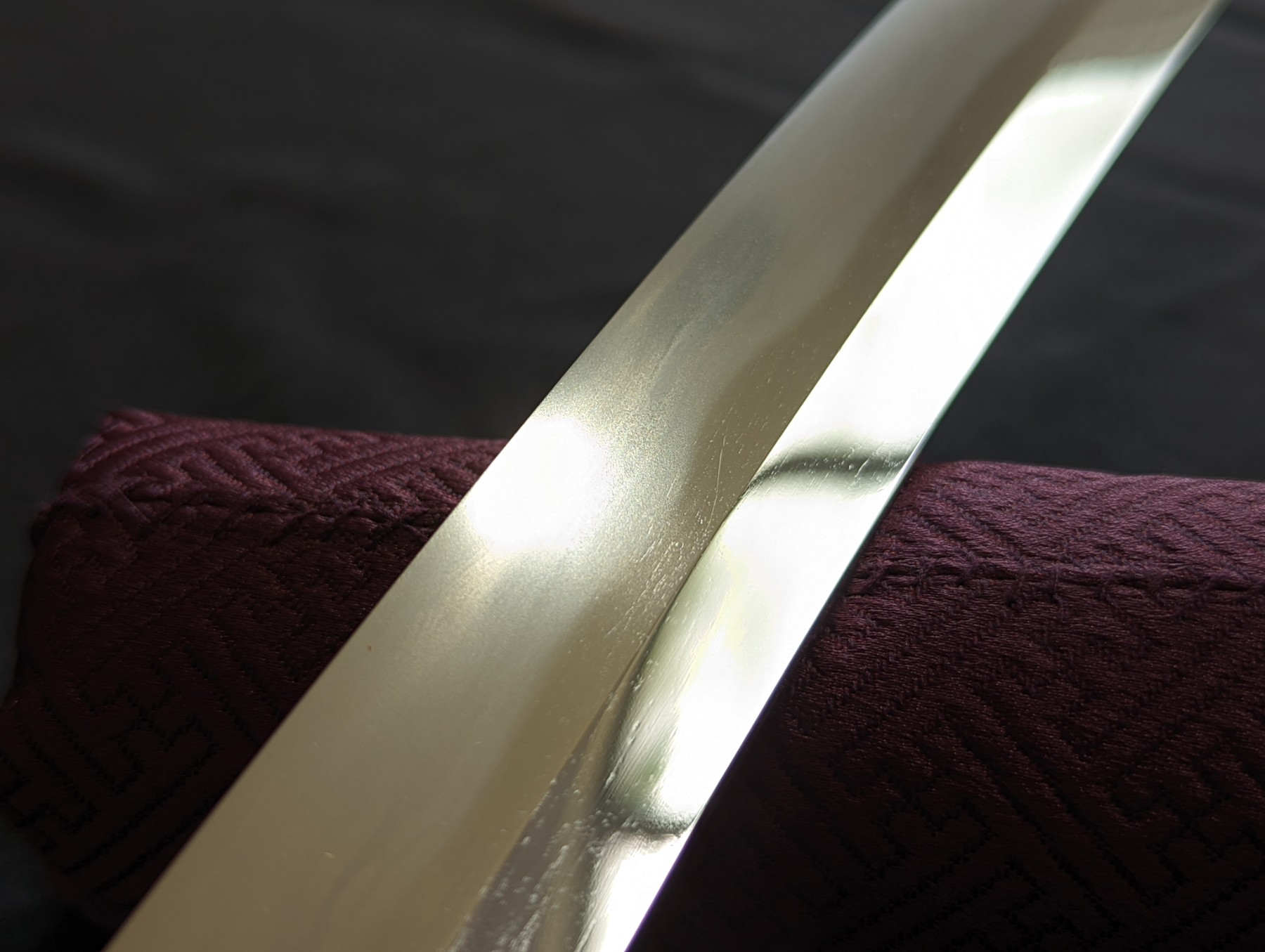

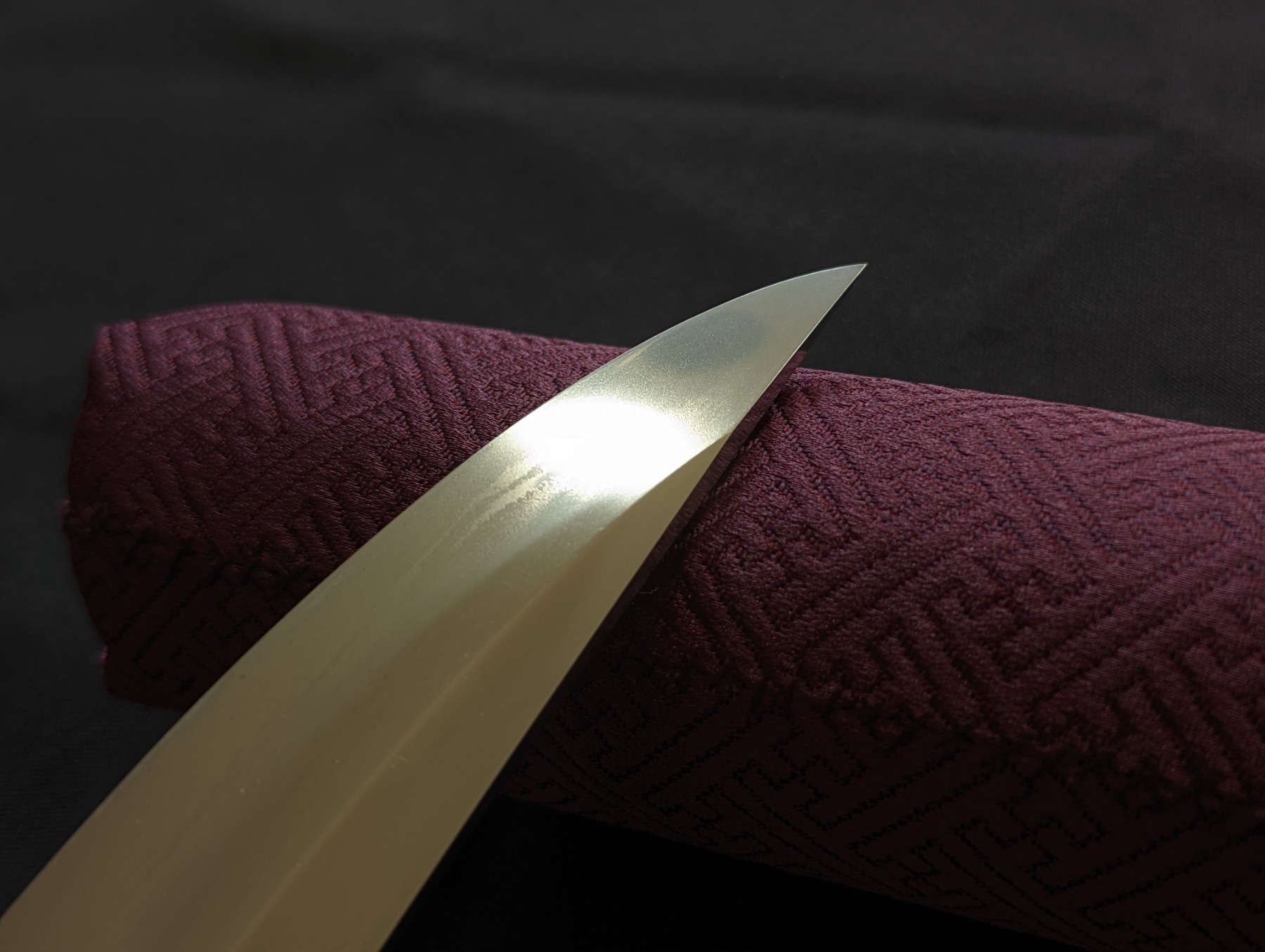

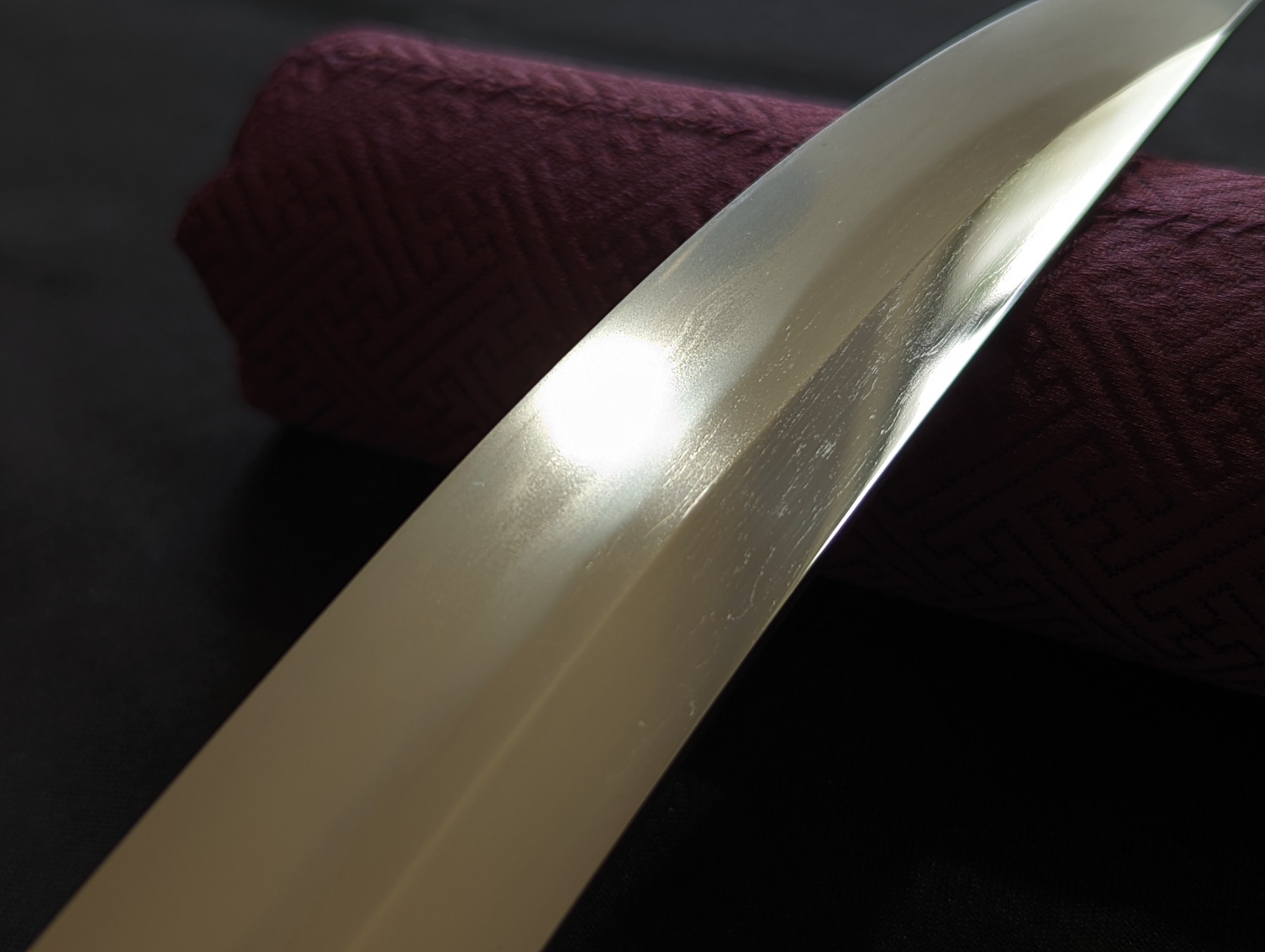

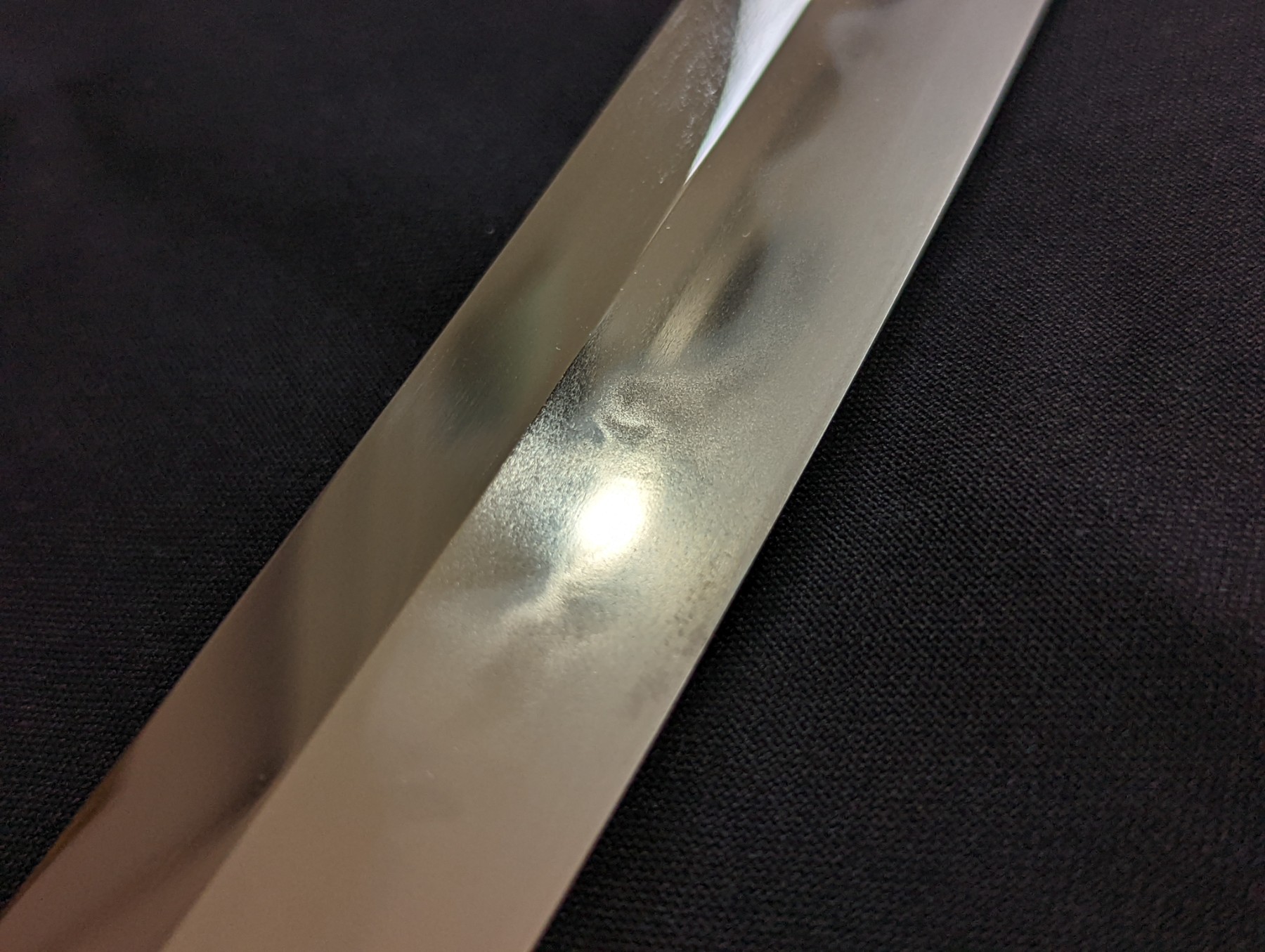

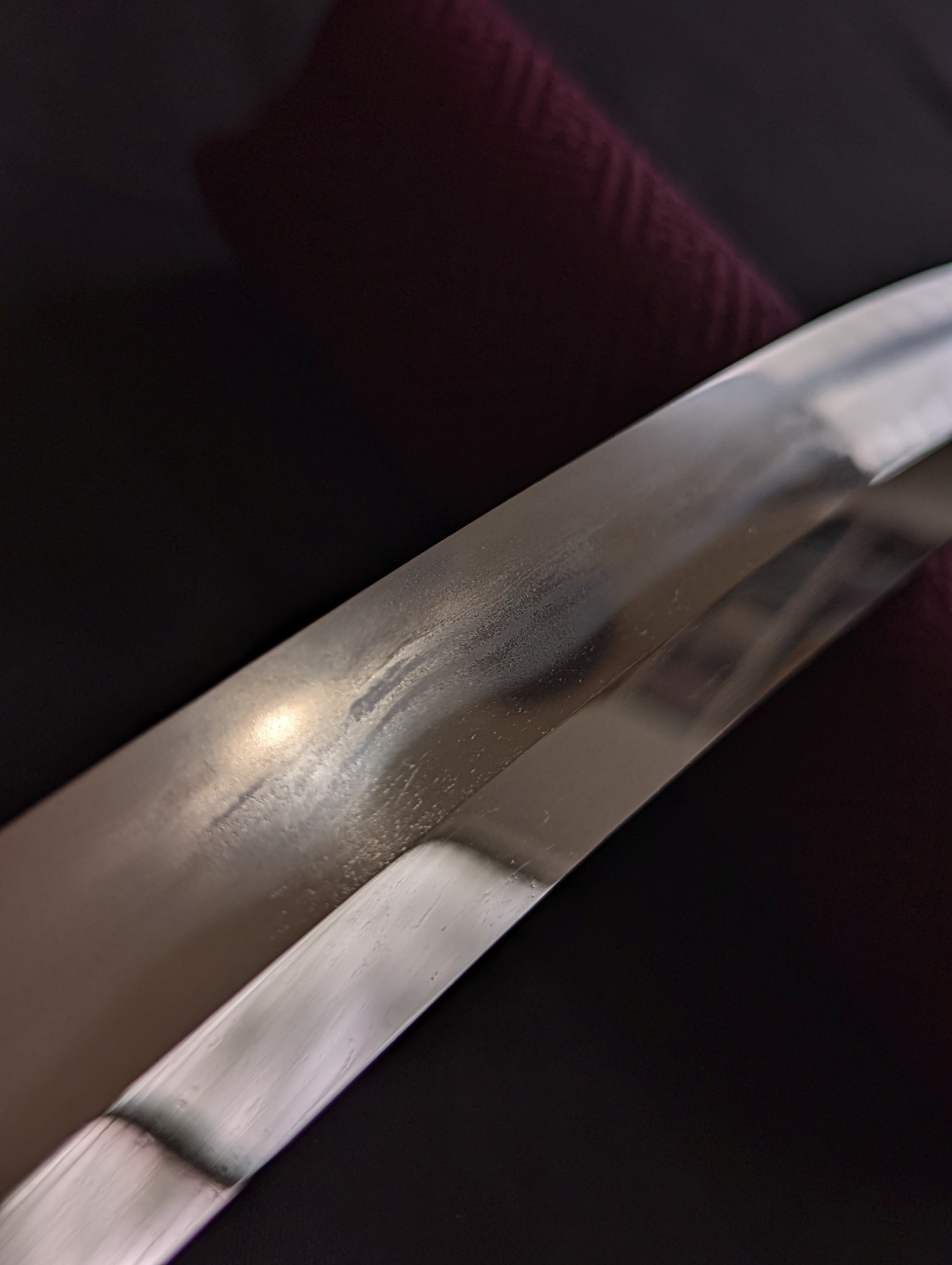

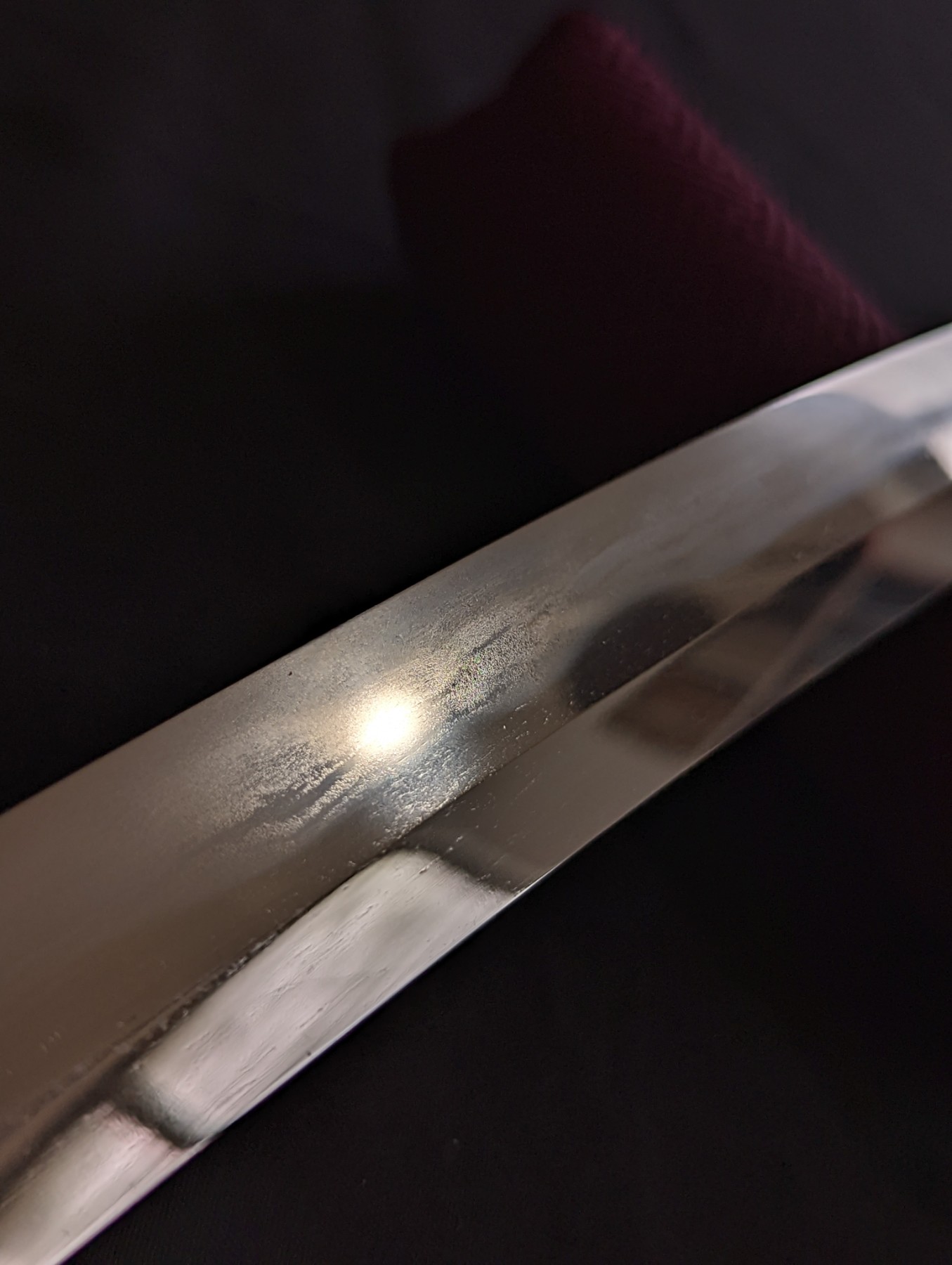

Dewa-daijo Kunimichi’s dated blades are seen from the Keicho (1596-1614) to Kanbun (1661-72) periods. As far as we know today, his active period extended over 50 years. Because of this, his blades are seen with Keicho Shinto to Kanbun Shinto shapes. From his signature styles, this katana is supposed to have been made during the Meireki period (1655-57) or somewhat earlier or later, but the shape is a Kambun Shinto shape. The jihada is itame mixed with mokume, the hada is visible and called a zanguri (rough) jihada. The hamon is ko-notare mixed with gunome, togariba, and yahazu choji.

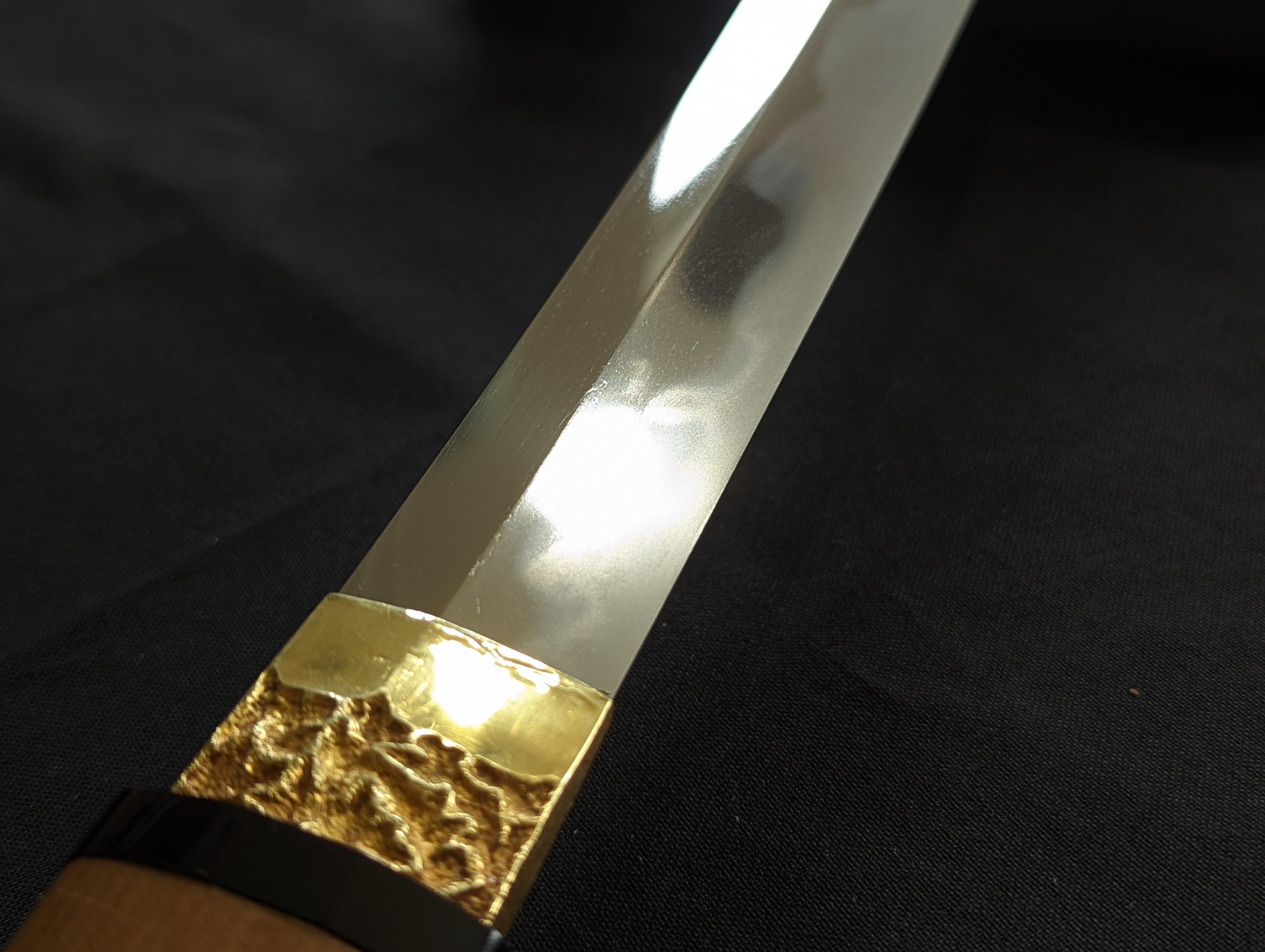

This is an extremely interesting sword, with a wide gunome-chogi on one side and the other is more Shizu-based with long streams of nie. In shirasaya with tsunoguchi and a gold foil habaki. Two sets of NBTHK papers. Formerly from the collection of Arnold Frenzel.

KUNIMICHI (国路), Genna (元和, 1615-1624), Yamashiro – “Heianjō-jū Kunimichi” (平安城住国道), “Dewa no Daijō Fujiwara Kunimichi” (出羽大掾藤原国道), “Dewa no Daijō Fujiwara Rai Kunimichi” (出羽大掾藤原来国路), “Dewa no Daijō Kunimichi” (出羽大掾十一辻). He was first a student of Iga no Kami Kinmichi (伊賀守金道) but studied later also under Horikawa Kunihiro (堀川国広). He signed his name in his early years with the characters (国道). Another one of his early signature variants, (十一辻) for Kunimichi, is a wordplay: “Kuni” can also be written with the characters “nine” (ku, 九) and “two” (ni, 二), added-up “eleven” (十一). The character (辻) is read tsuji and has the meaning “road,” but road can also be written with michi (道・路). Sources that do not know this wordplay quote the reading of the characters (十一辻) for “Kunimichi” therefore incorrectly as “Jūichitsuji.” After his studies under Kunihiro, and at the latest from the 14th year of Keichō (1609) onwards, he signed his name Kunimichi with the characters (国路). The name change is probably not connected with the receiving of the honorary title Dewa no Daijō because he signed this title also in combination with the variant (国道) for Kunimichi. Kunimichi was active over a very long period of time. We know dated signatures from the 13th year of Keichō (慶長, 1608) to the second year of Kanbun (寛文, 1662) which makes at least 55 years. But regardless of this long artistic period, Kunimichi is also considered as one of the most productive smiths of the Horikawa school. His year of death is unknown but there exists a date signature of the fifth year of Keian (慶安, 1652) with the information “made at the age of 77” which calculates his year of birth as Tenshō four (天正, 1576), And the latest extant date signature is from the ninth month of Meireki three (明暦, 1657) and is combined with the information “made at the age of 82.” This signature is finely chiselled and it is therefore assumed that the blade is one of his latest works. The exact date when he received his honorary title Dewa no Daijō is not known. The earliest blade signed that way is dated with the eighth month Keichō 20 (1615). Therefore it is assumed that he received the title around Keichō 19 or 20. His use of the character “Rai” (来) in some of his signatures alludes to a connection to the Mishina school as certain Mishina smiths signed with Rai too. Another support for this theory is that he signed his name during his early years with the Mishina-michi (道). Kunimichi was active over a very long period of time. We know dated signatures from the 13th year of Keichō (慶長, 1608) to the second year of Kanbun (寛文, 1662) which makes at least 55 years. But regardless of this long artistic period, Kunimichi is also considered as one of the most productive – and also best – smiths of the Horikawa school. Thus we find blades with a Keichō-shintō-sugata and such with a foretaste of a Kanbun-shintō-sugata. We know works in the Keichō-shintō style of Kunihiro but his strong point was a flamboyant hamon with variation in the height and depth of the yakihaba and excellent nie and nioi-based hataraki. When working in the shintō style he forged a dense ko-mokume and the hamon is here an ō-gunome-midare that bases on an ō-notare, but also an ō-gunome-midare or gunome-midare is seen. Partially the gunome elments are densely arranged and look like single midare elements. The bōshi is a ko-maru agari that tends to midare-komi. When he worked in the Yamato tradition he forged a mokume mixed with a noticeable amount masame. The hamon is in this case a chū-suguha in ko-nie-deki with uchinoke and the bōshi is ko-maru or ko-maru agari. jōjō-saku