Description

During the middle of the Kamakura period, Bizen swordmaking was dominant, and saw the rise of great smiths in Fukuoka (Ichimonji), as well as Osafune (Mitsutada and Moriie). Mitsutada is considered the founder of the Osafune school which would last into the Shinto period. Moriie is the founder of the Hatakeda school though he seems to have worked in Osafune as well. Hatakeda is a town adjacent to Osafune or else a subdivision of Osafune itself. Moriie is ranked at Sai-jo saku by Fujishiro for grand-master skill levels, and is rated at 2,000 man yen in the Toko Taikan. These place his level as equal to Rai Kunitoshi and Rai Kuniyuki.

“Moriie is called ‘Hatakeda Moriie’ since he lived in Hatakeda of Bizen Province, though there is no extant work of Moriie of which signature includes ‘Hatakeda Ju’. [However, there are] some extant works with ‘Osafune Ju’. Therefore it appears that Hatakeda was a section of Osafune Village or the Hatakeda school was merged with the Osafune school afterwards. It is natural that Moriie demonstrated a similar (and gorgeous) workmanship to those of Mitsutada and Nagamitsu of the Osafune school, but gunome and distinct kawazuko-choji are more emphasized in his hamon.” – NBTHK Token Bijutsu

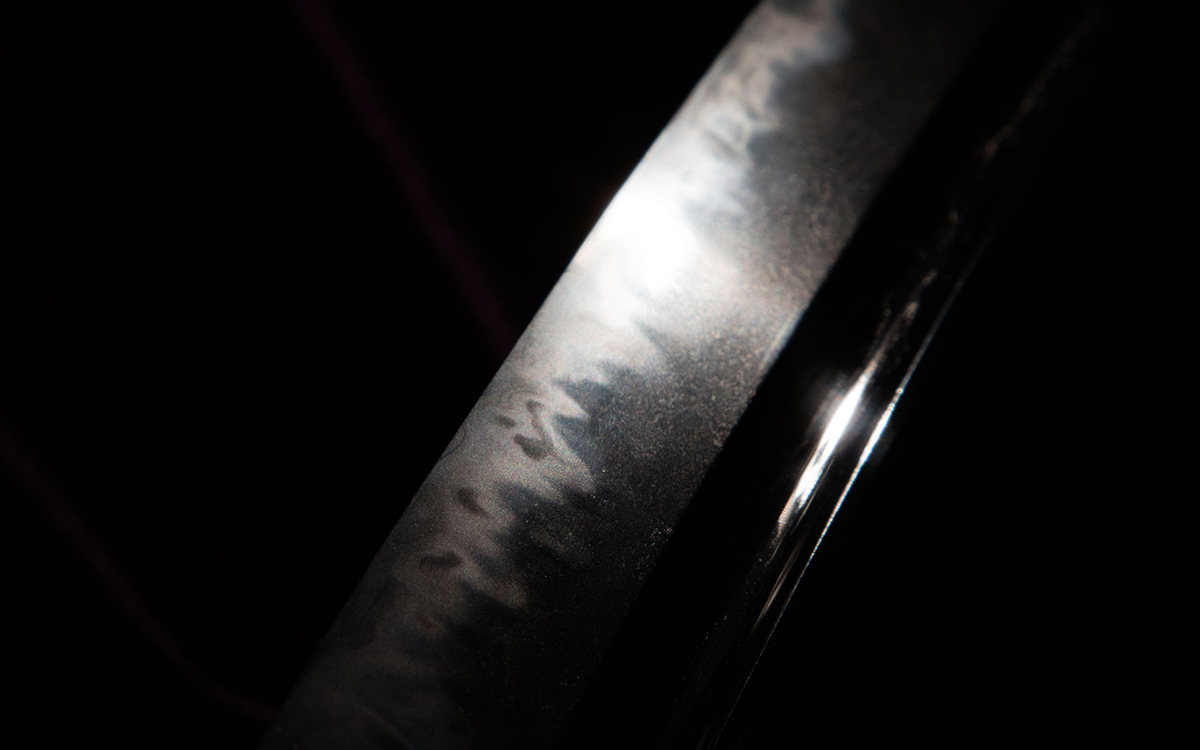

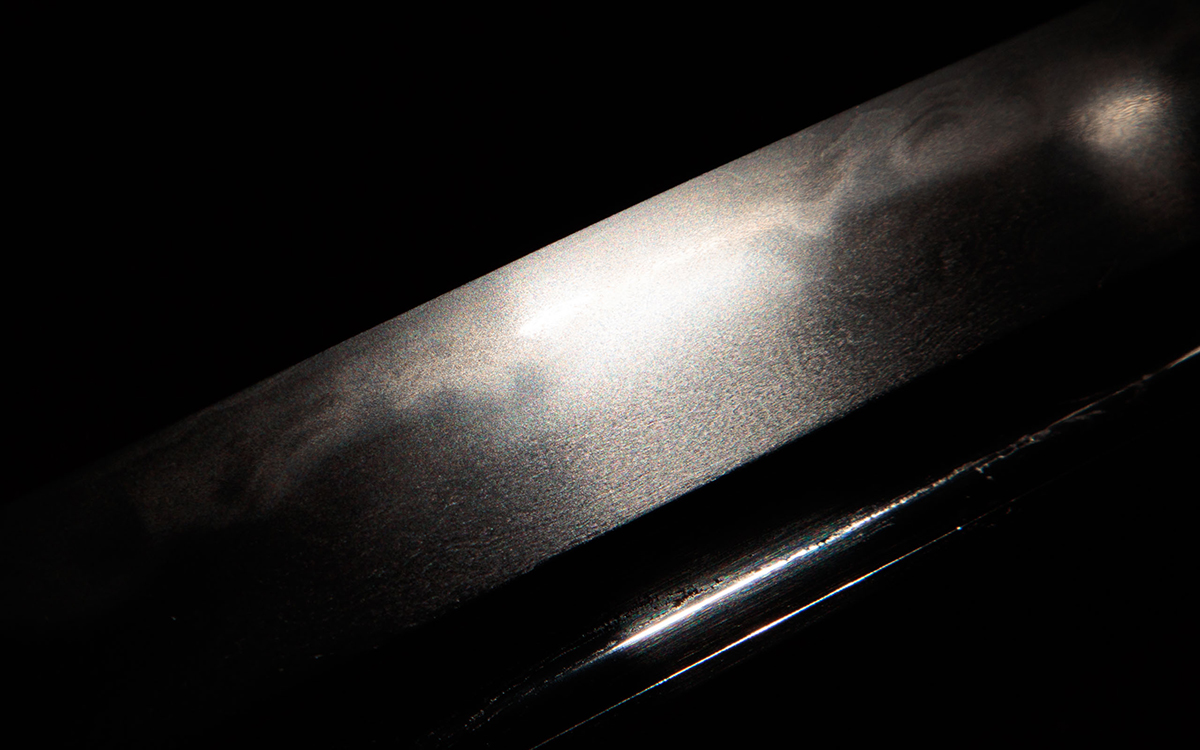

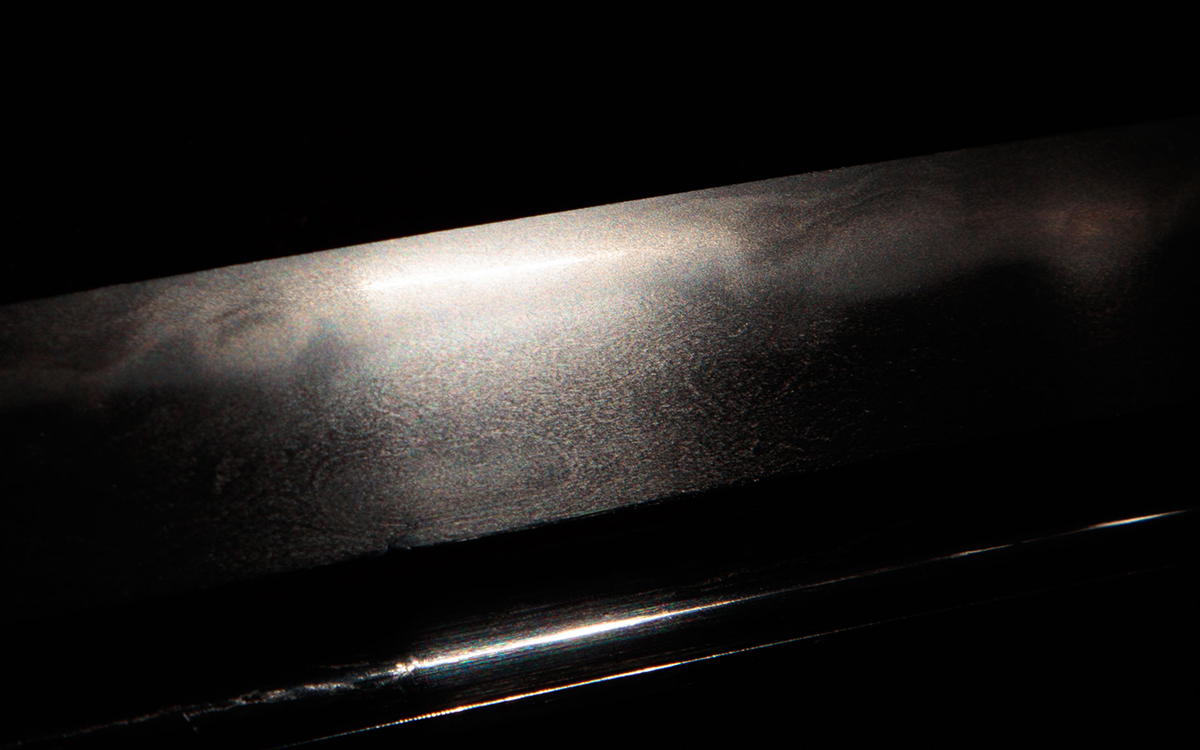

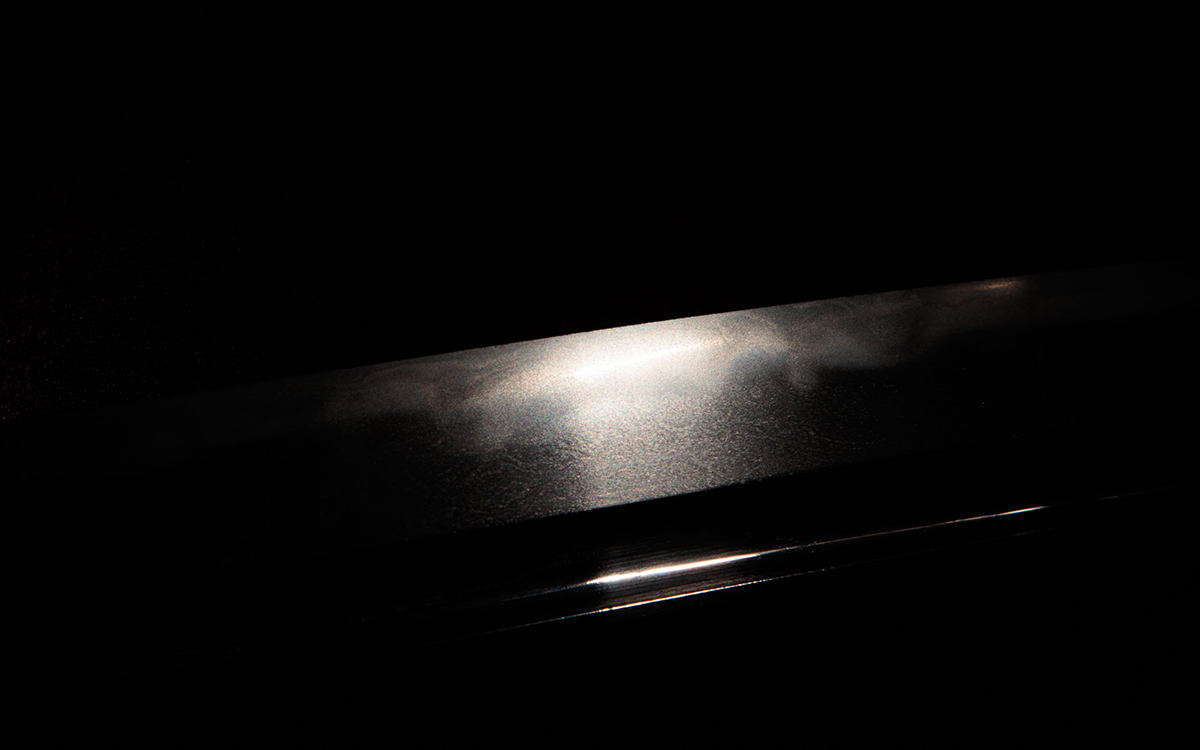

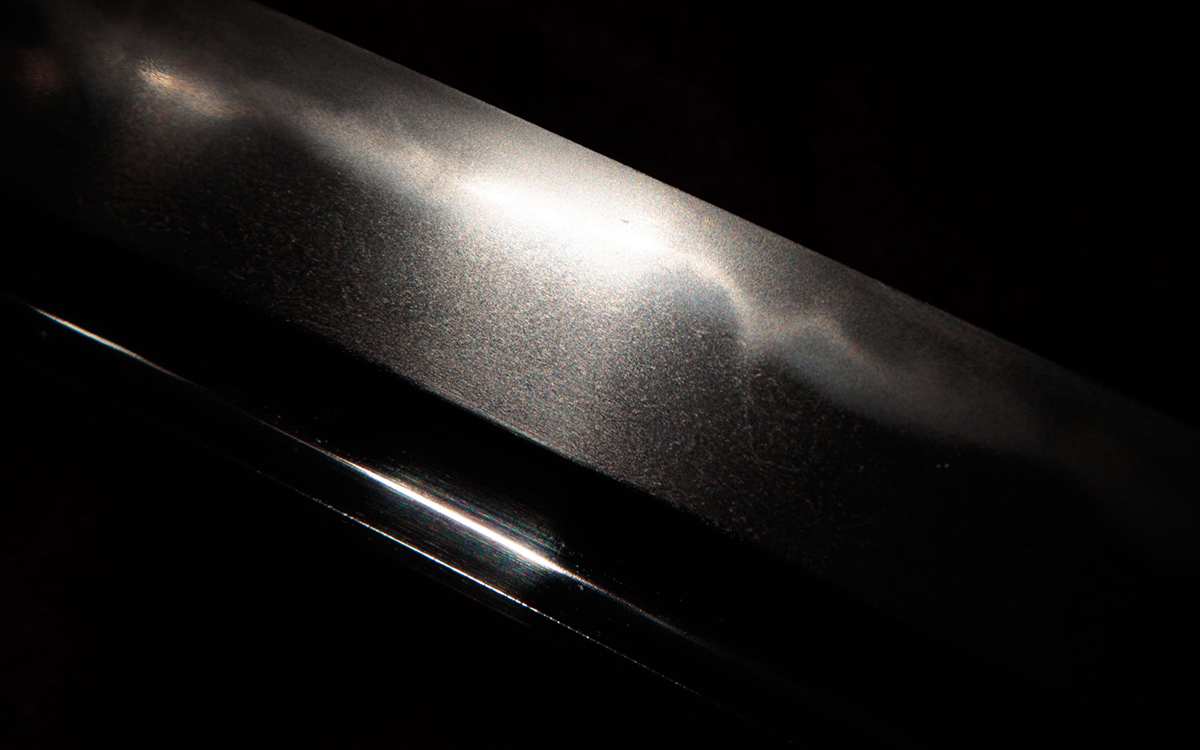

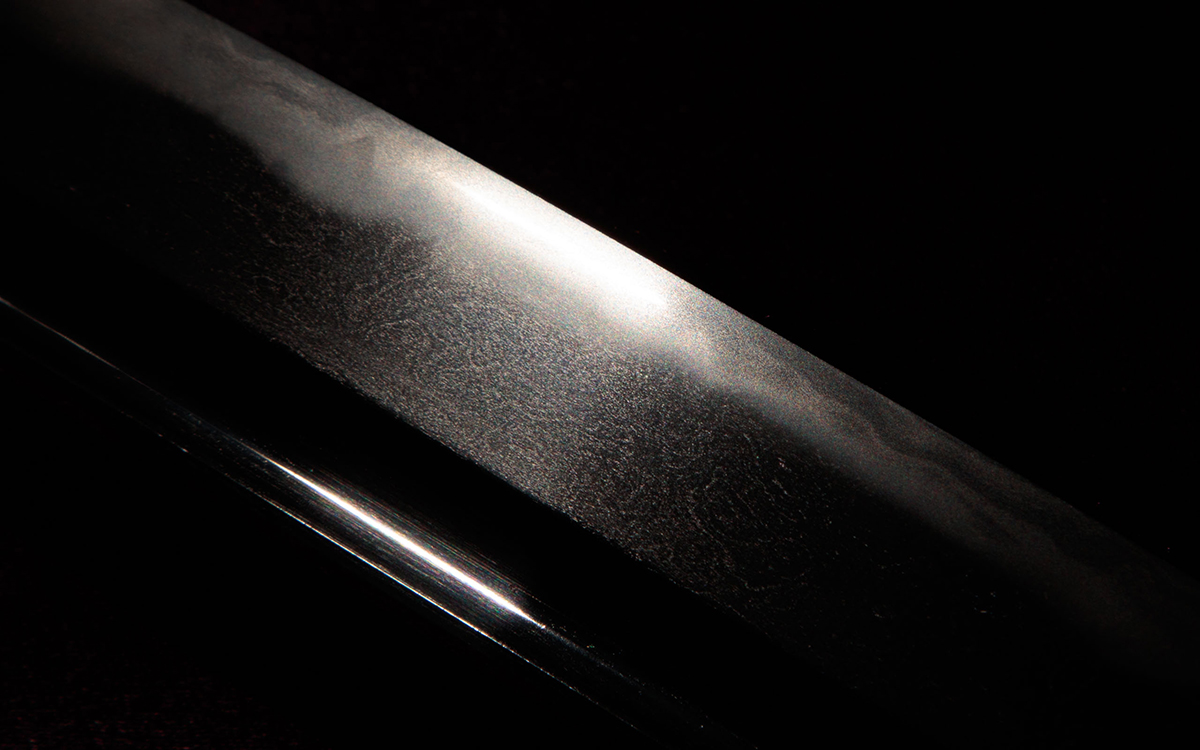

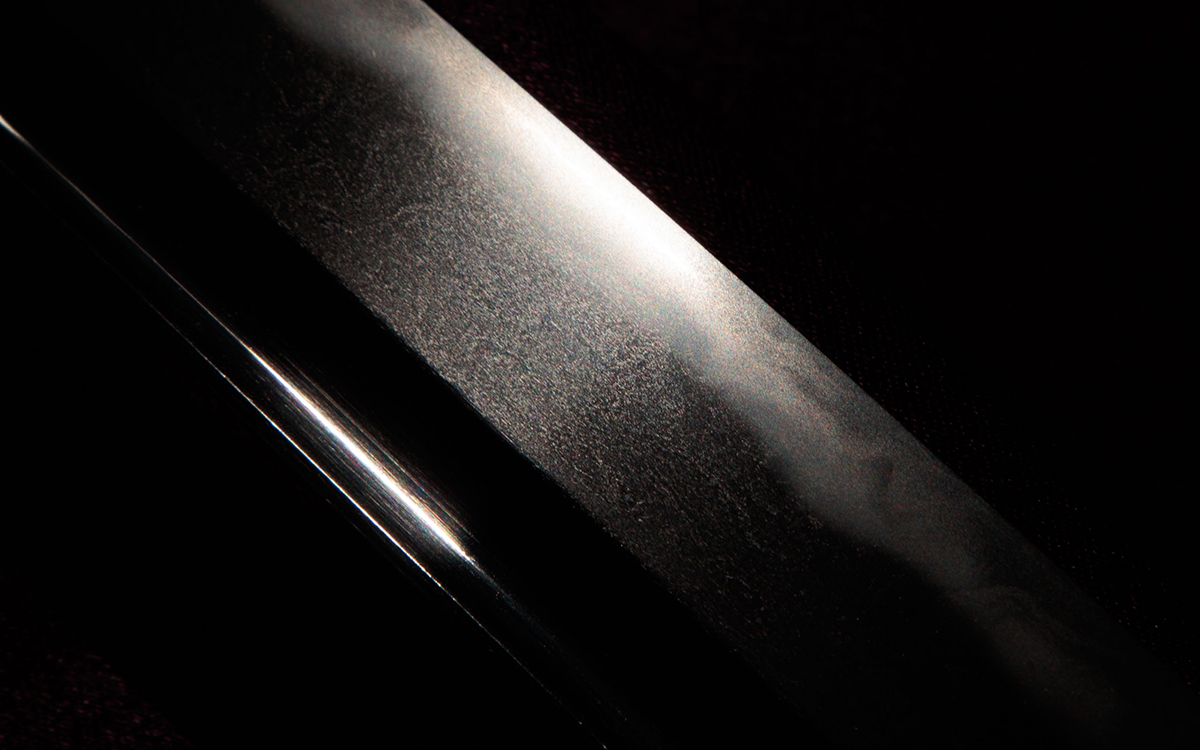

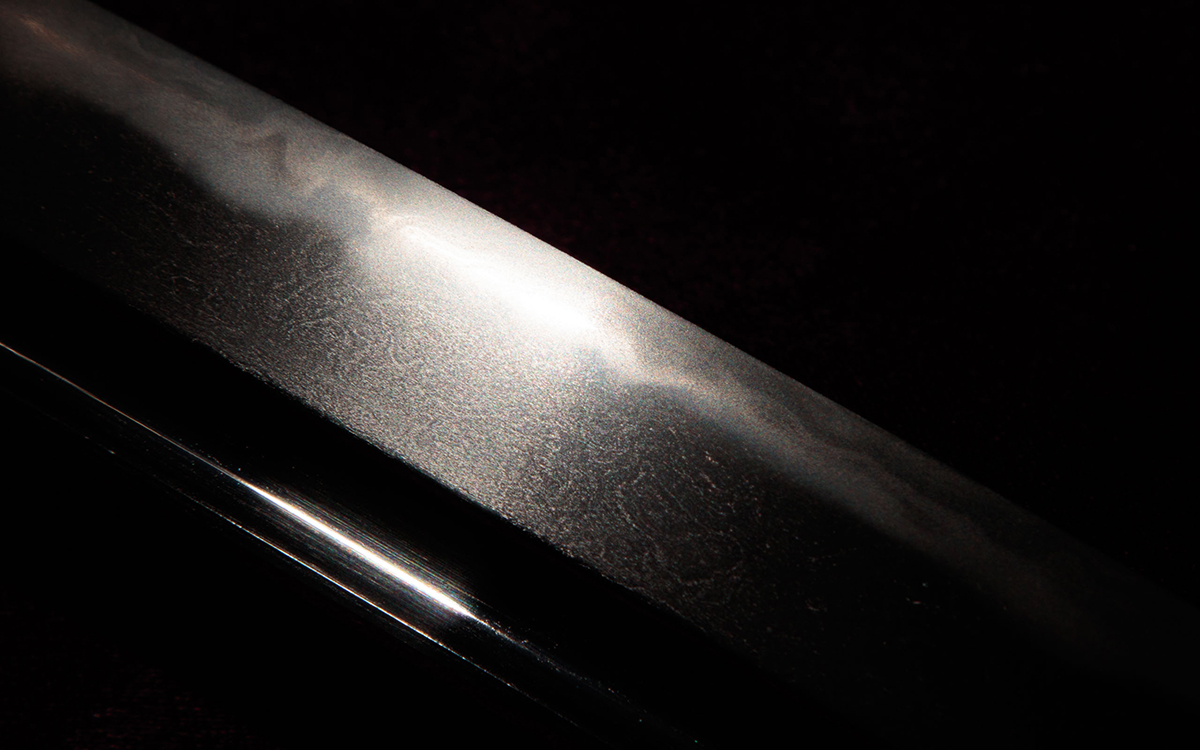

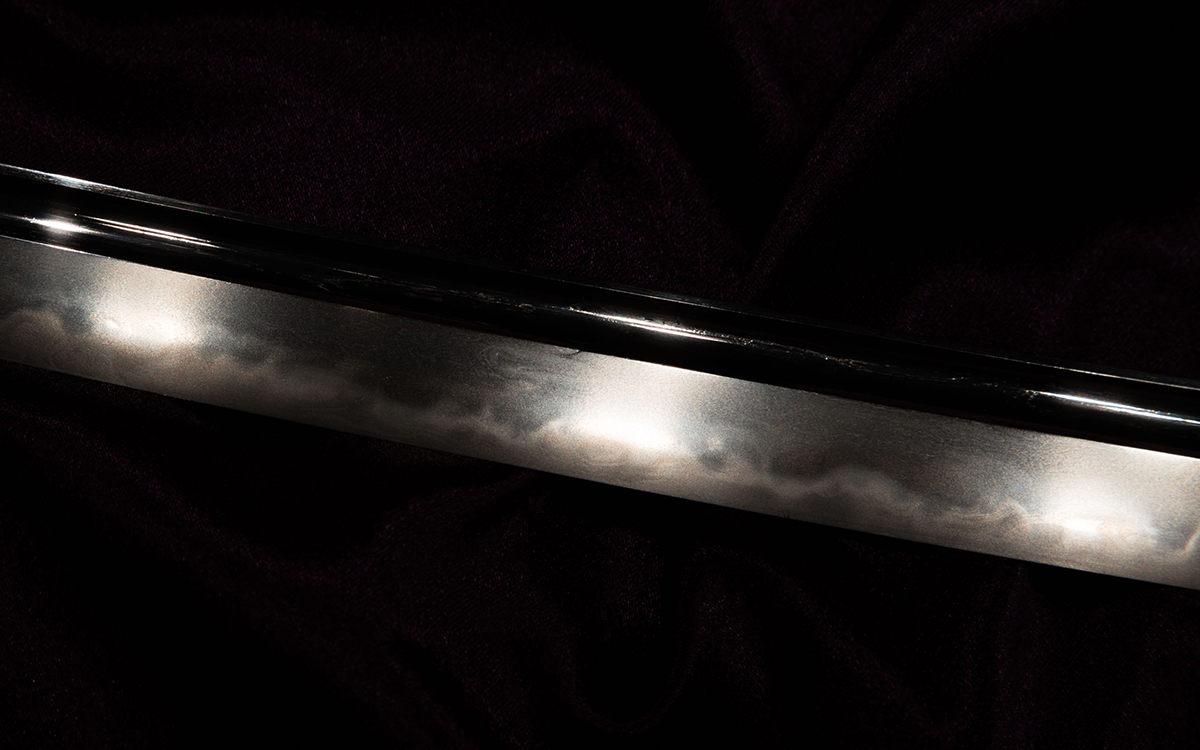

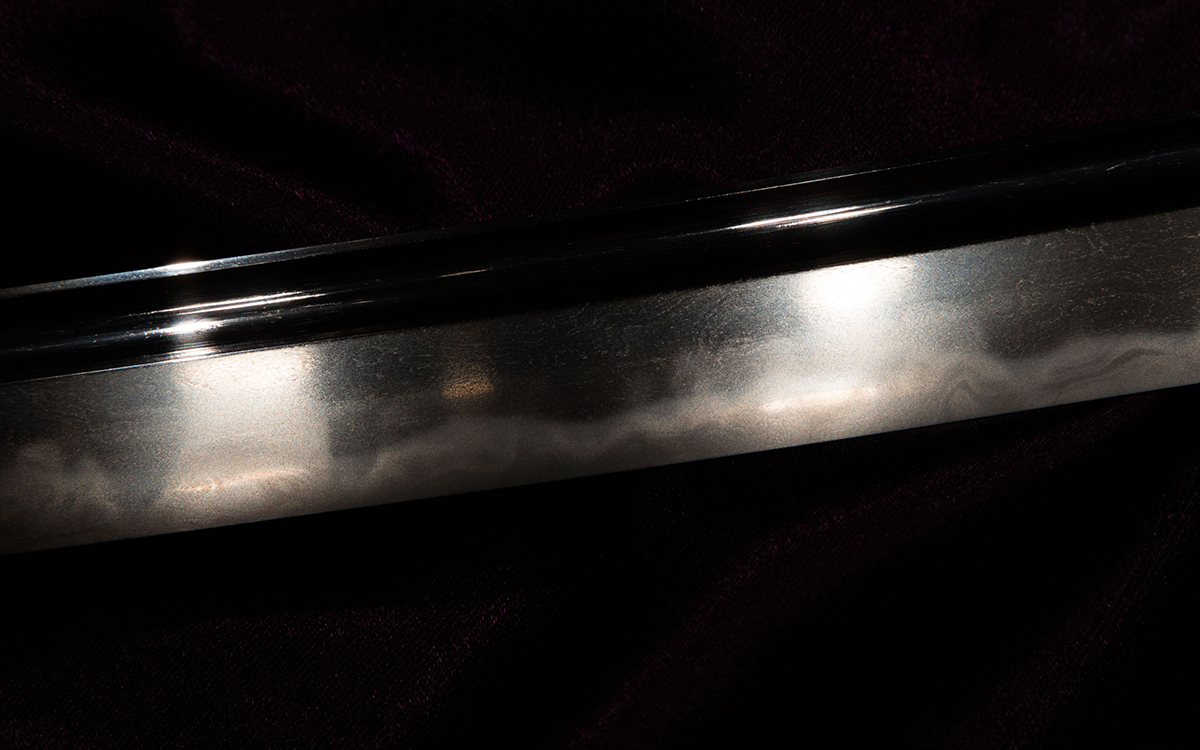

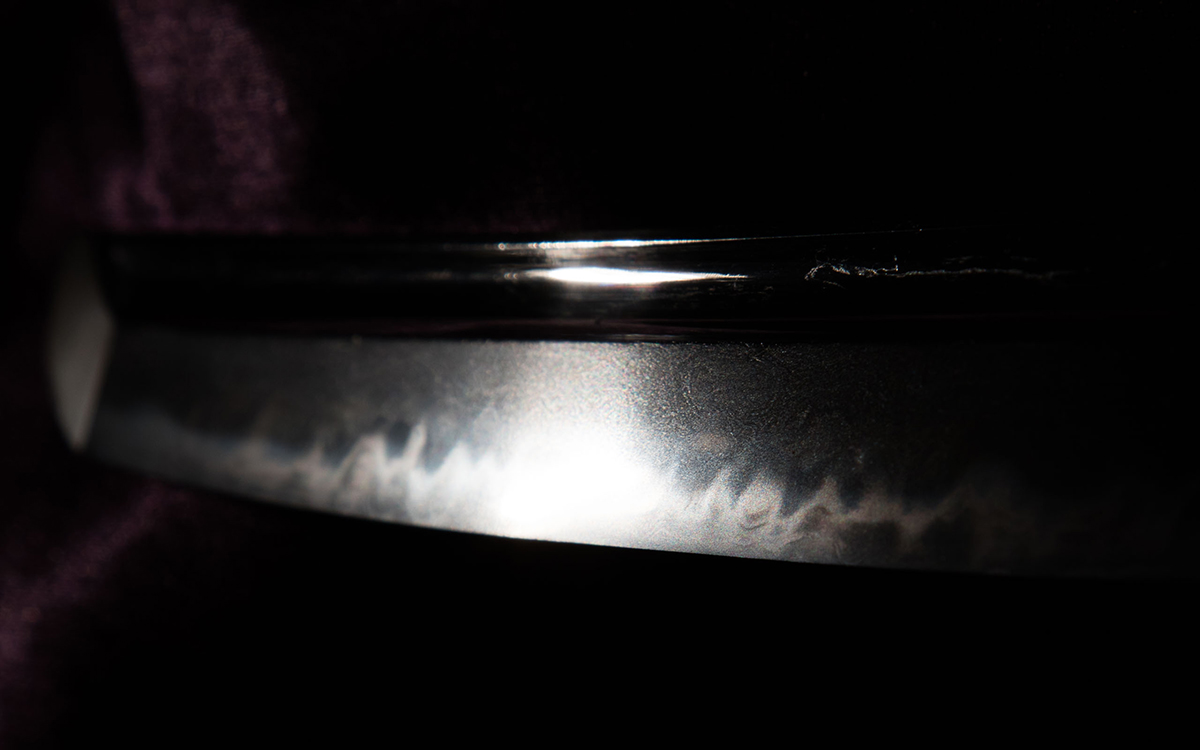

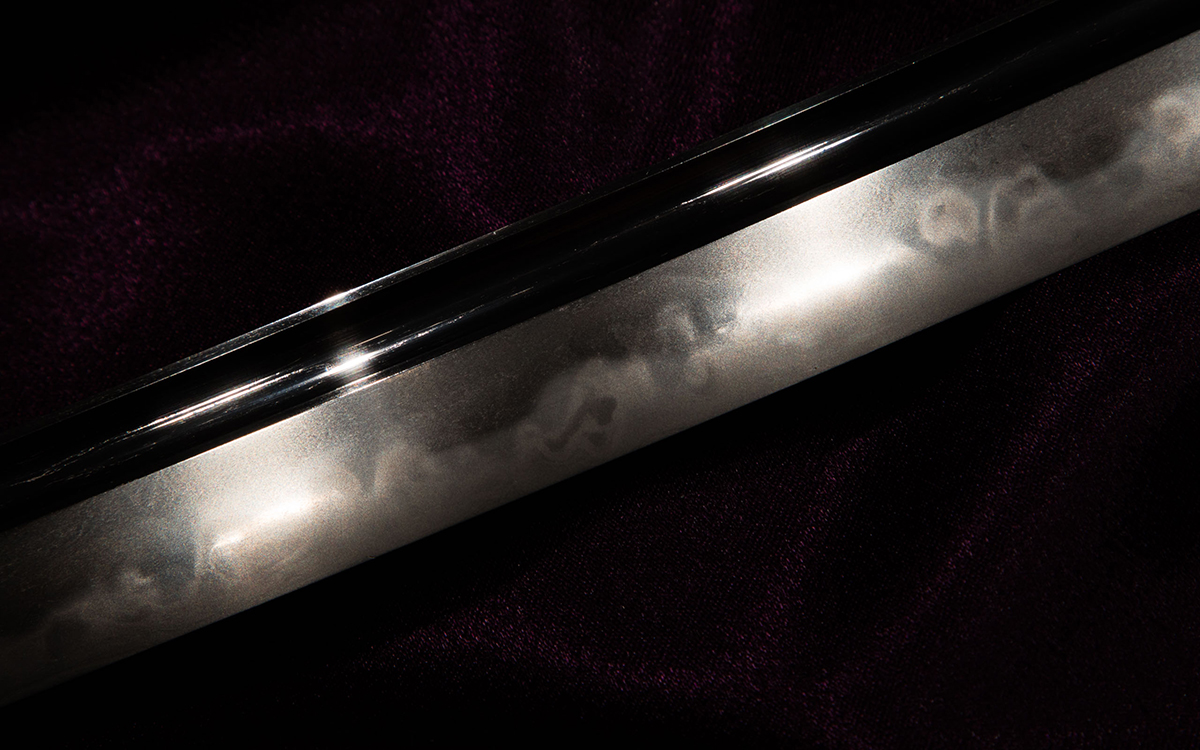

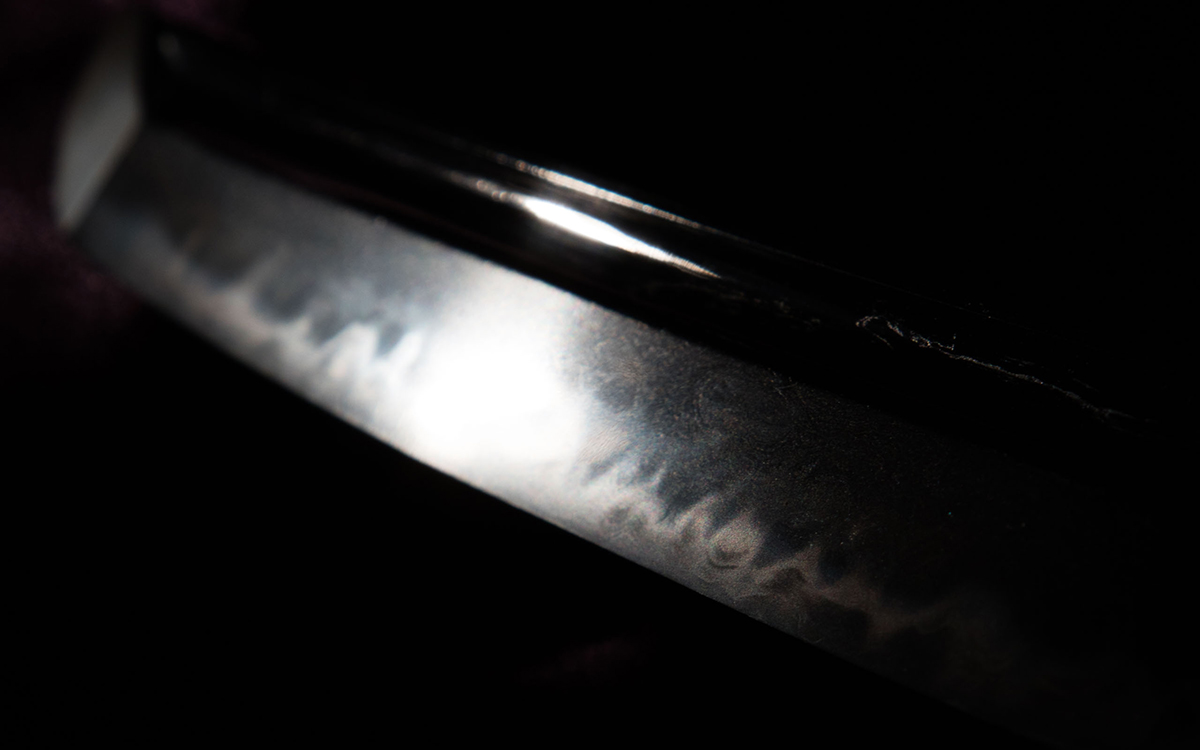

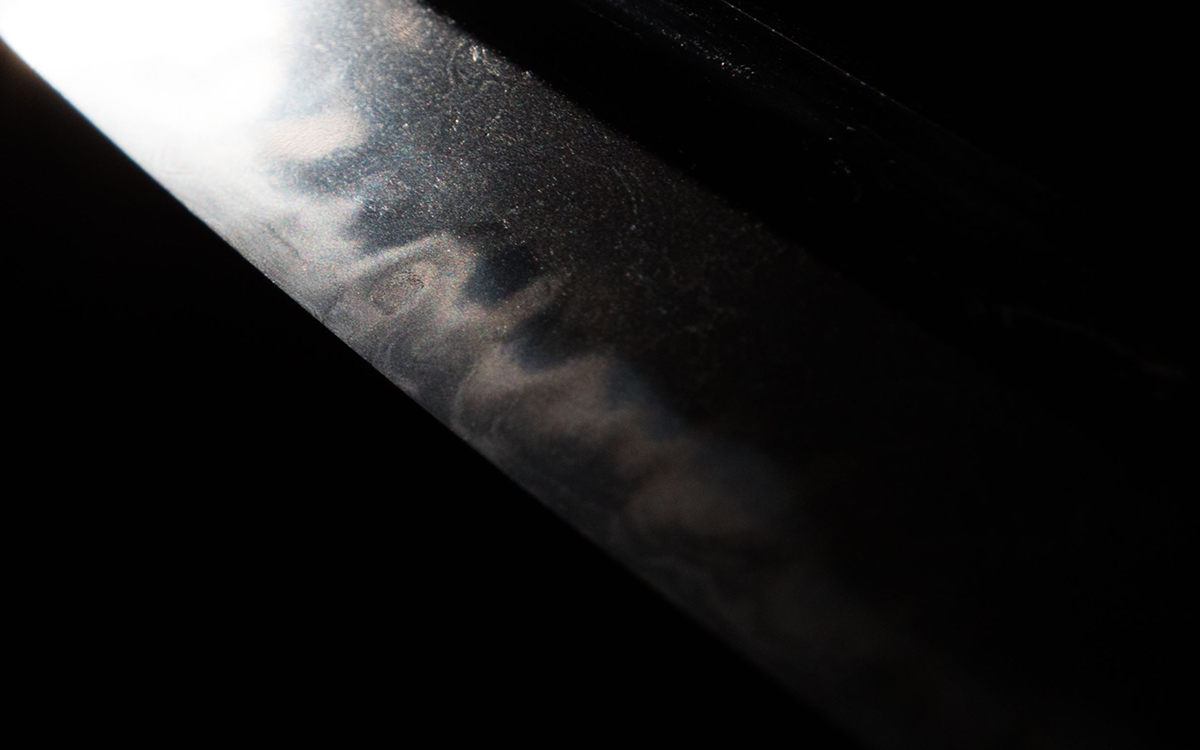

Both Moriie and Mitsutada worked in similar forms to the Fukuoka Ichimonji smiths. They make a florid choji midare hamon with utsuri, and the sugata is masculine with a squarish ikubi kissaki and a wide body throughout the blade. Moriie is famous for a particular style of choji where the head of the choji separates off from the body underneath it (tadpole choji, or kawazuko). His forging follows a style of itame that stands out clearly.

“Moriie is a representative smith of this school [Hatakeda], and is a famous person who should be compared in stature with Mitsutada. […] It is said that the large mei are the shodai, and the small mei are the nidai, but even if it is one with a small mei like the one in the Tokyo National Museum, they are splendid works that are not inferior to those with a large mei. […] As for the mei on the pieces that are thought to be by the shodai, there are three types: Moriie, Moriie Tsukuru, and Moriie (kao).” – Nihonto Koza

Moriie’s father is said to be a smith called Morichika of the Fukuoka Ichimonji school, but this smith’s works are now lost. Moriie would give his name to several following generations, as well as teaching other master smiths such as Sanemori and Morishige. Sanemori left dated work of 1277 and 1289, and is supposed to be a son or grandson of Moriie. Morishige’s student was Motoshige, the second generation of which would also be very famous and is thought to be one of the Sadamune Santetsu (three great students of Sadamune).

As for Moriie, there are some arguments as there usually are between first and second generation work, with some advocating for one smith and others for a two smith theory. The difference is that the second generation is sometimes thought to mostly sign in a smaller signature. Tanobe sensei does not necessarily agree with this partitioning only on the size of the signature. However it is more strongly held that a long signature style starting with Osafune ju is certainly work of the second generation.

“It seems evident, therefore, that the size of the mei does not necessarily determine as to which generation Moriie’s works belong to. Some say the different sizes all represent one and the same smith at different times. This point needs clarification pending further research.” – Tanobe Michihiro, NBTHK Token Bijutsu

There are dated works ascribed to the second generation which place him close to 1280, so the first generation or at least the first period of Moriie corresponds to a time around 1259 as is found in old books. Some have three Kamakura generations of Moriie, and in that case his work may begin as early as 1232. Second generation work can also be singled out by a slender shape to the sword as well as a hamon based more on gunome than on choji. These are features more similar to Nagamitsu, with the Shodai’s work being more similar to Mitsutada. The NBTHK has in the past separated Moriie generations by denoting works of Moriie (implicitly the first generation), then explicitly noted second generation, and all others are marked as a group of “later generation” works.

“Moriie – Nidai: There are only tachi, I have yet to see a tanto. Generally speaking, the tachi have slender mihaba in comparison to that of the shodai.” – Nihonto Koza

Many of Moriie’s works are famous and were owned by the top daimyo families, and were given as gifts to and from the Shogun. A typical example that was owned by the Tokugawa Shogun Ieyasu is documented in the Token Bijutsu:

“This tachi is not listed in ‘Kyoho Meibutsu Cho’ but has been well known as ‘Hyogo Moriie’. The nickname comes from Marumo Hyogo no Kami Nagateru who was a retainer of Saito Tatsuoki and he was retained by Oda Nobunaga after his lord was killed by Nobunaga. His son, Chikayoshi was in the side of Ishida Mitsunari and fought for the Toyotomi family in the Battle of Sekigahara. He was temporarily hiding in Mt. Koya after the Toyotomi family and its league were defeated by Tokugawa Ieyasu then escaped to Kaga Province. He changed his name to Marumo Doho and was retained by Maeda Toshitsune over there. This tachi was presented to Tokugawa Ieyasu by the Koyasan Temple afterwards. It is supposed that Marumo Hyogo no Kami Nagateru donated it to the temple when he was hiding in Mt. Koya. The sword was given to Tokugawa Yoshinao who is the first generation of the Owari Tokugawa as a memento of Tokugawa Ieyasu when he died then it has been inherited by the Owari Tokugawa family for generations.” – Token Bijutsu

There are 50 Juyo works by Moriie (all generations though 35 of these are first generation). Six of those that passed Juyo went on to pass Tokubetsu Juyo. Another 9 works are Juyo Bijutsuhin. Three works of his were Kokuho before the war, and are now included amongst 12 total Juyo Bunkazai. All of this says that Moriie is deeply respected, and his work is quite difficult to come by as the total existing that are legal to export from Japan is relatively small.

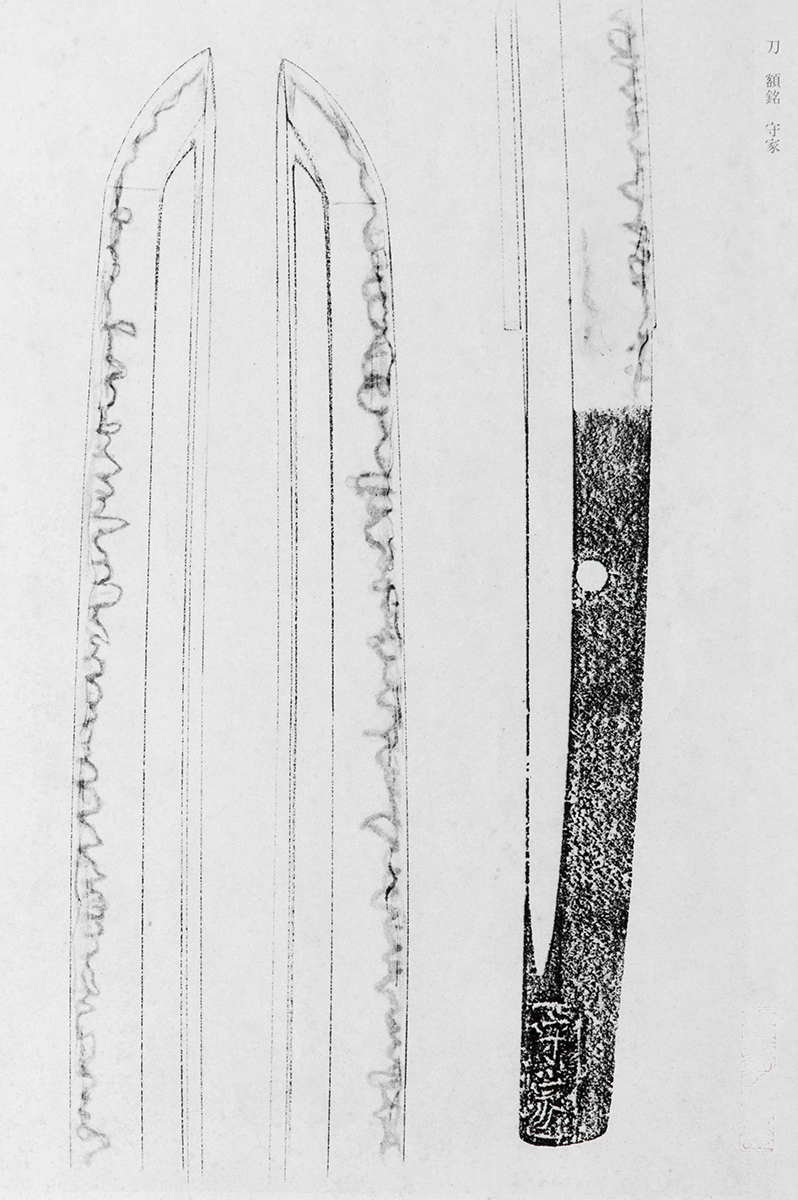

Moriie Tachi

This is a rare and beautiful blade by the first generation Hatakeda Moriie. It shows the classically gorgeous, natural-looking work of the middle Kamakura period. It has been shortened but the signature was retained as gakumei by insetting it into the new nakago. The blade would have been around 85cm originally which is about right for a middle Kamakura tachi. The NBTHK compares it to contemporary work by Mitsutada.

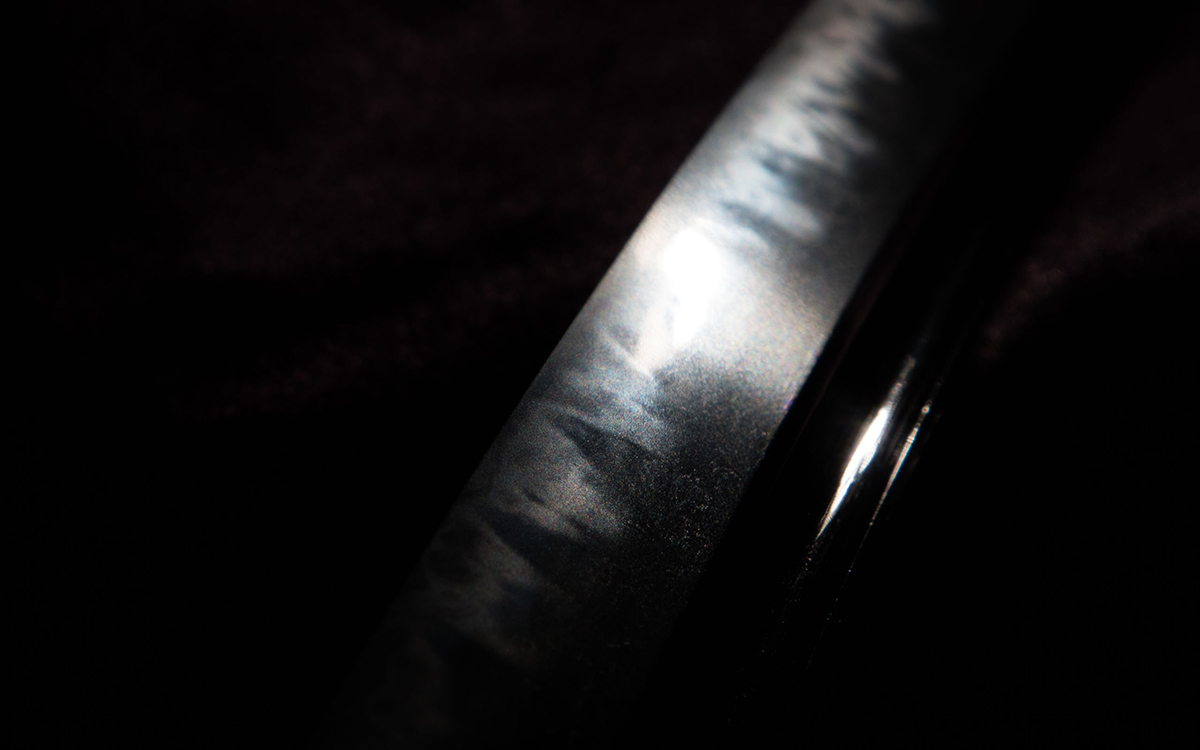

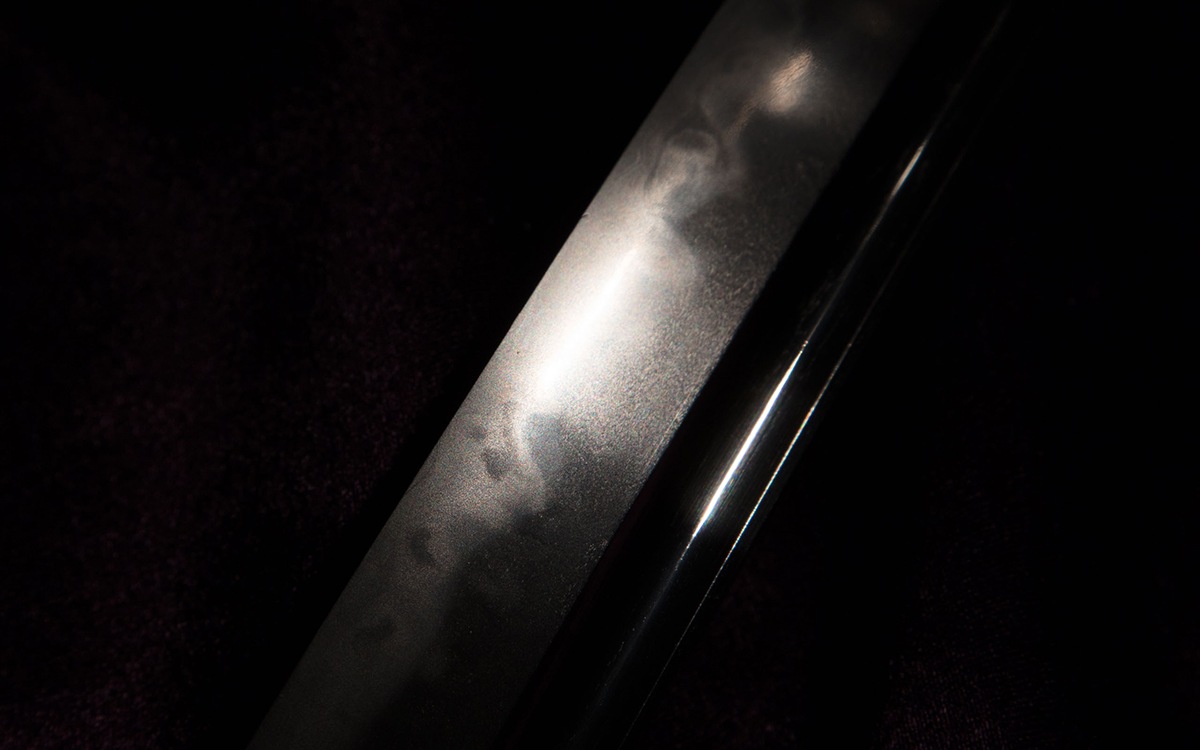

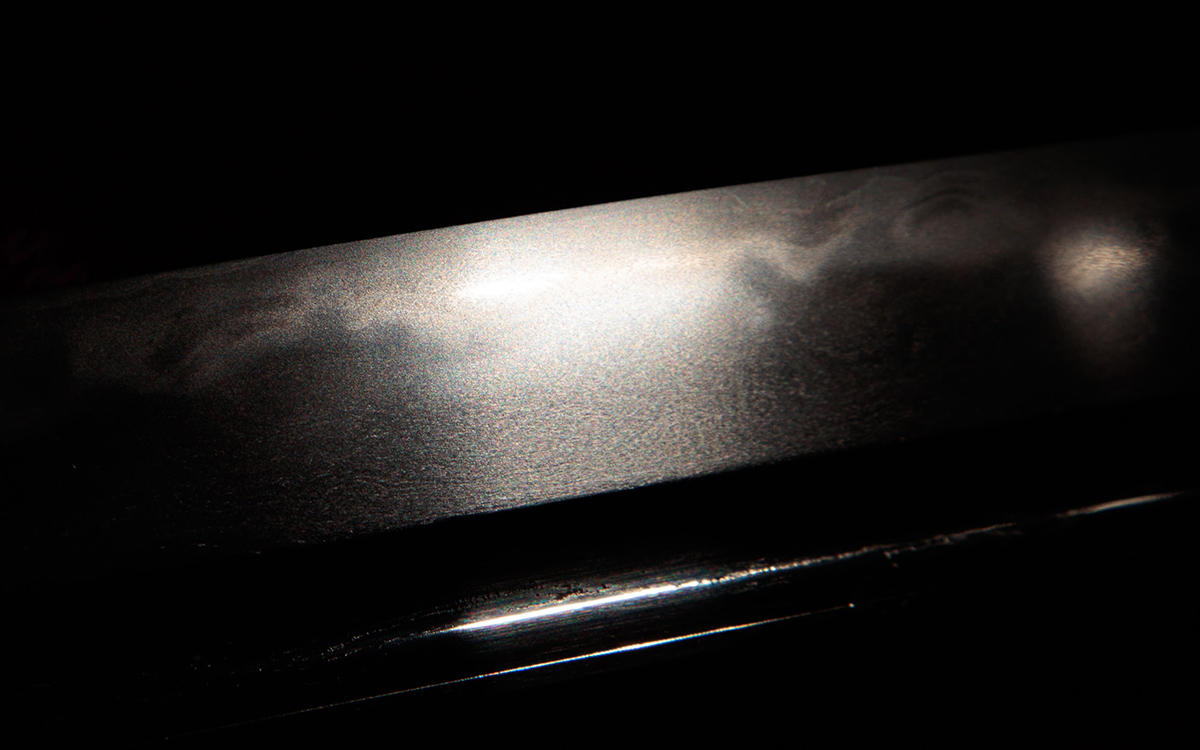

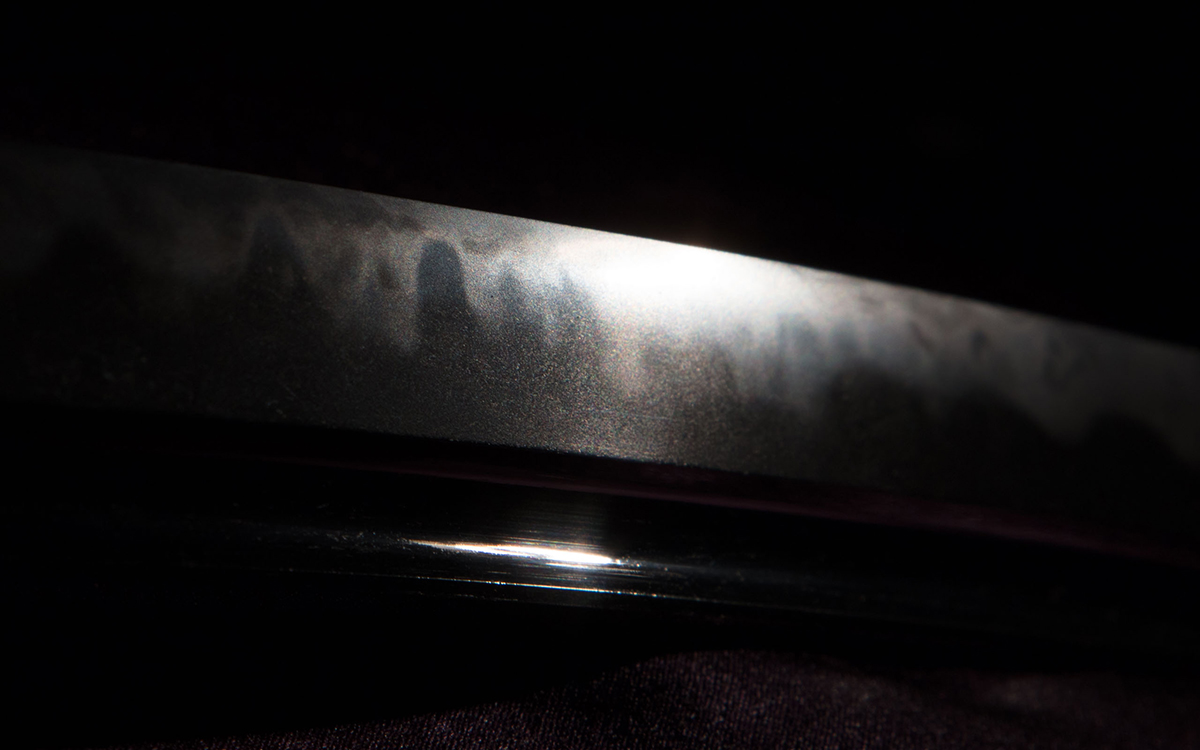

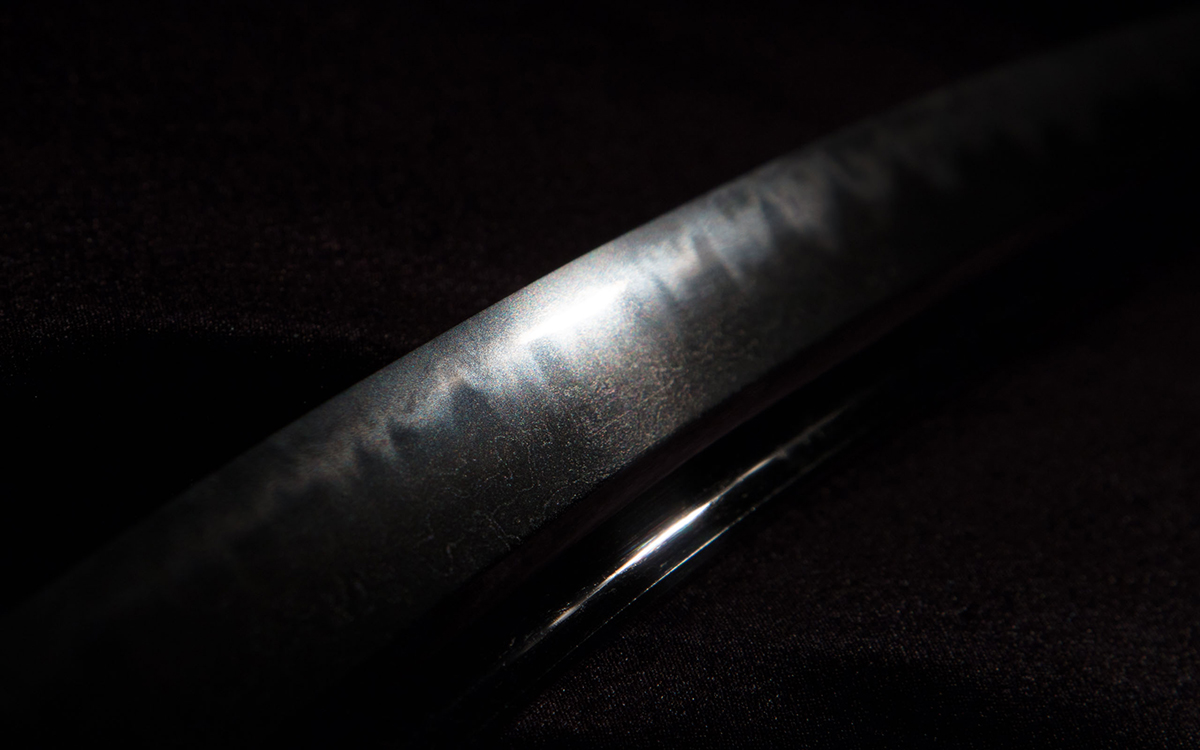

A nice feature of this tachi is that it retains a deep curve and the robust shape of archetypal middle Kamakura works. The kissaki is squarish ikubi kissaki in shape, and the blade begins wide and doesn’t taper all that much compared to more elegantly shaped late Kamakura swords. It’s not so common to find middle Kamakura blades that fit the archetypal shape so well as this one does (polishing tends to alter the shape over time and they begin to lose their distinct shapes if the polisher hasn’t carefully attended to preserving it).

The description of Moriie’s work from Albert Yamanaka matches this sword perfectly.

“(Hamon) Very closely resembles that of OSAFUNE MITSUTADA Worked in NIOI with the pattern in 0-CHOJI-MIDARE with the width of the HAMON varying greatly from one section to the next. Those made wide will have the peaks of the CHOJI reaching up and touching the SHINOGI, whereas those made narrow will be close to touching the cutting edge. There is a variety in the workings and the blade has much vigor.There will be KAWAZUKO CHOJI mixed in too. The grain of the steel within the HAMON will tend to stand out. Also, there will be much NIOI ASHI made long with NIE clustering around them. In some cases, there will be TOBIYAKI at the HAMON edge. This is not the kind oi TOBIYAKI seen on other works. These are the result of the tip of the CHOJI having become disconnected, that is the root of the CHOJI having been made so narrow, that it was cut off.” – Albert Yamanaka, Nihonto Newsletters

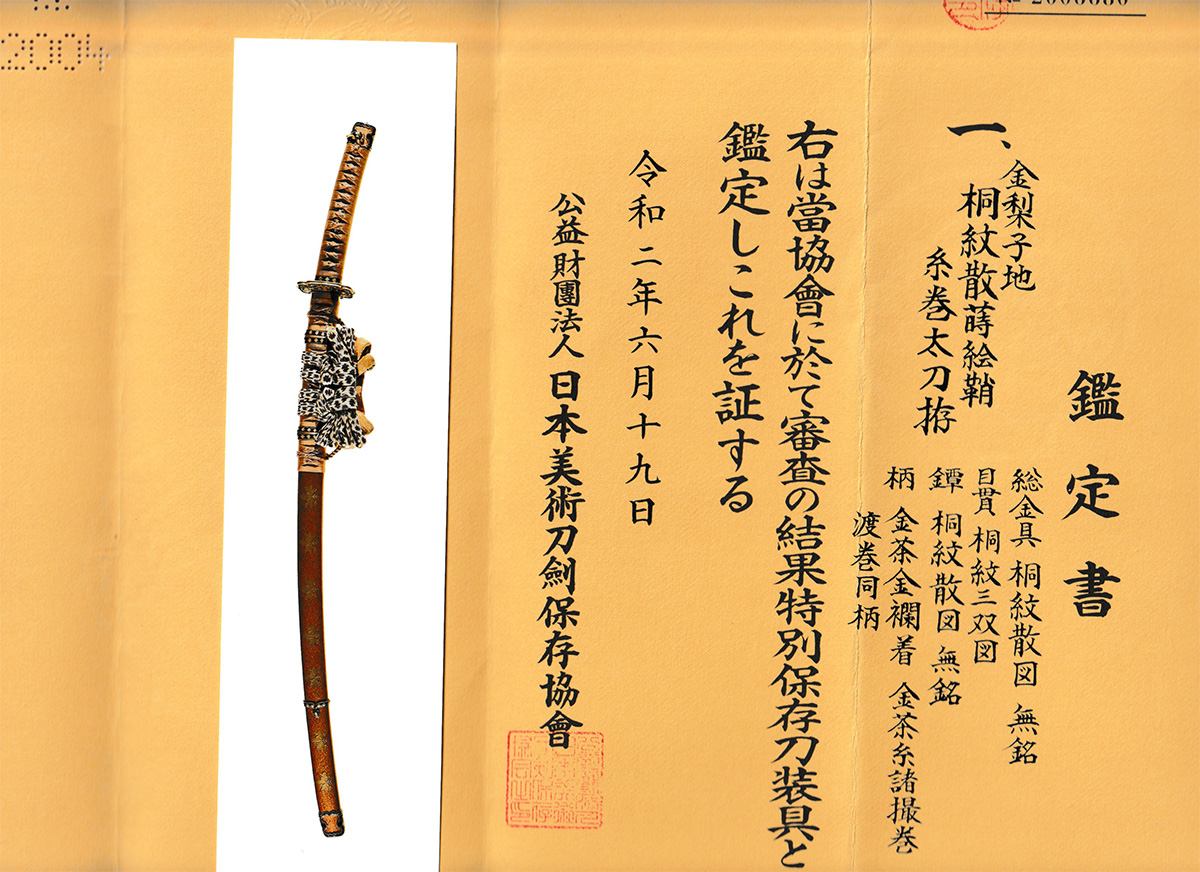

I bought this sword from the collection of an old Japanese collector in November of 2016, and it is the first time it’s been made available in the west. The blade is also accompanied by fine quality late Edo period tachi koshirae in gold makie lacquer bearing kirimon. This form of lacquer is very difficult to make and not everyone can make it today, as it requires special skill. The koshirae are papered Showa 31 which is 1956 and are Tokubetsu Kicho. This level of paper is no longer recognized due to scandals in the 1970s and has been replaced by Tokubetsu Hozon. However, papers this old are not in doubt or question since they predate Juyo even (they were the top paper at the time of their issuance). The NBTHK was founded in 1948 and began issuing Tokubetsu Kicho in 1950. So this is quite an early paper and authenticates the koshirae as an antique. The blade has a sayagaki that comes from the same timeframe too: Sato Kanzan made it in 1958.

The blade itself an old Juyo from 1967, before Tokubetsu Juyo existed. At this time then, to be granted Juyo status was the top level that a sword could achieve and these old Juyo are held in high esteem.

The hallmark kawazuko choji can be found in the hamon, which otherwise is quite similar to Fukuoka Ichimonji. The hamon is bright and very dynamic, and together with the signature, middle Kamakura shape, and fine koshirae, this would be an excellent acquisition for someone interested in one of the major Kamakura grandmasters. Middle Kamakura period tachi by the top smiths that preserve the signature are very precious, and I am sure someone will cherish this wonderful set.

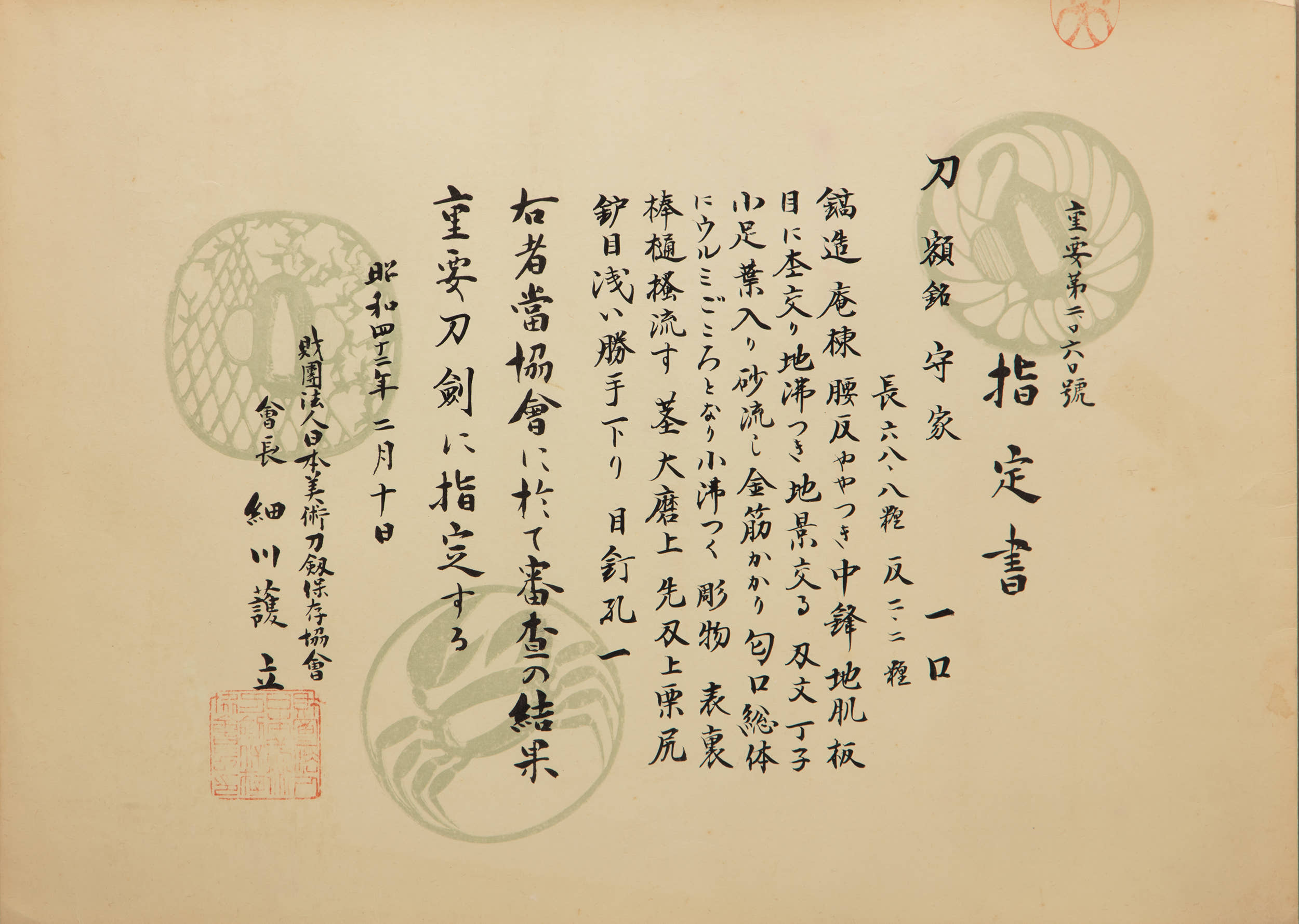

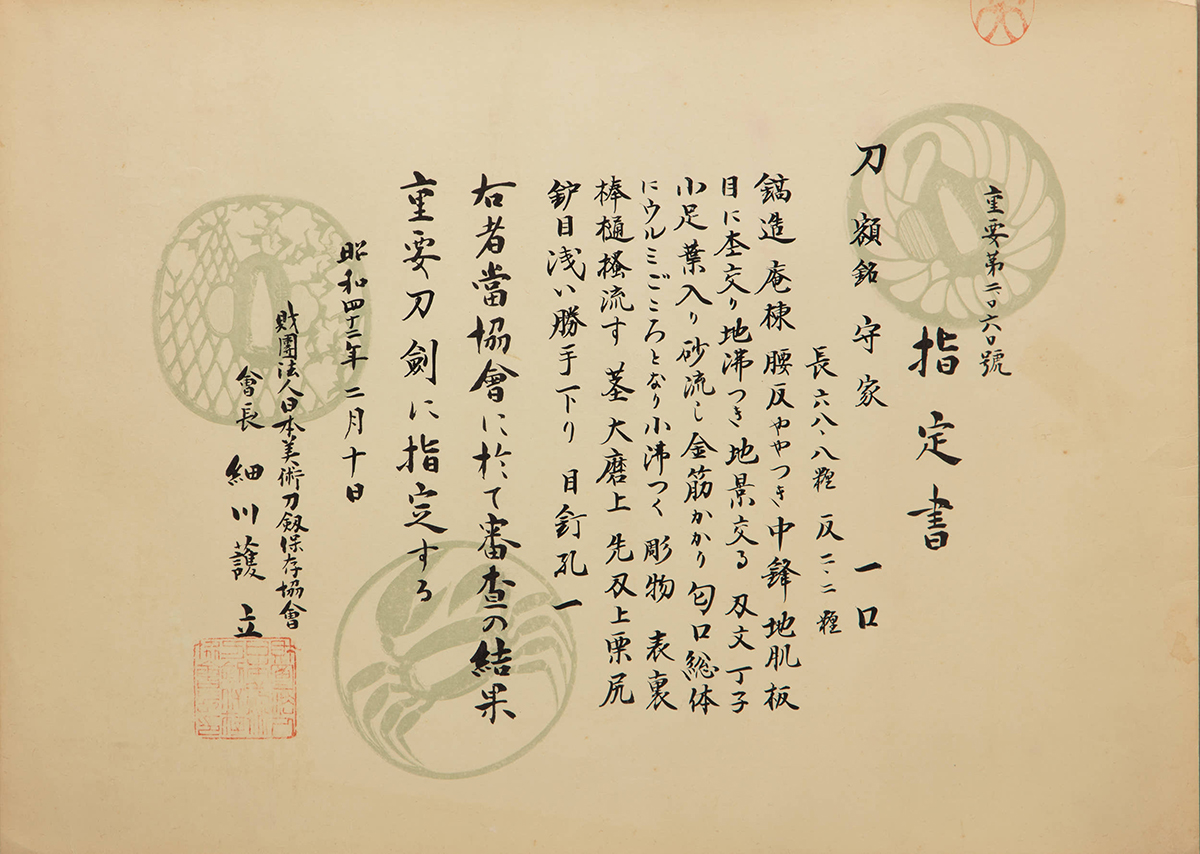

Juyo Token

Appointed on the 10th of February, 1967, session 15

Katana, Gakumei: Moriie

Keijo

shinogi-zukuri, iori-mune, rather deep koshizori, chû-kissaki

Kitae

itame mixed with mokume, in addition ji-nie and chikei

Hamon

chôji in ko-nie-deki that features a wide nioiguchi and that is mixed with ko-chôji, ko-ashi, yô, sunagashi, and kinsuji, the nioiguchi is overall a little subdued

Boshi

shallow midare-komi with a ko-maru-kaeri and hakikake

Horimono

on both sides a bôhi that runs with kaki-nagashi into the tang

Nakago

ô-suriage, ha-agari kurijiri, shallow katte-sagari yasurime, one mekugi-ana, the haki-omote side bears a “Moriie” gaku-mei at the tip of the tang

Setsumei

According to tradition, Moriie was a smith who lived in Hatakeda which was located close to the village of Osafune in Bizen province. There are no signatures known which bear the supplement “Hatakeda” but we know a dated blade from Bun’ei nine (文永, 1272) which is signed with “Osafune jû.” The workmanship is similar to that of the contemporary Osafune grandmaster Mitsutada. This blade is ô-suriage and bears a “Moriie” gakumei at the tip of the nakago, which is corroborated by the workmanship and the excellent deki (construction).

Sayagaki

This tachi bears a sayagaki by Dr. Sato Kanzan, one of the top scholars of the 20th century and one of the founders of the NBTHK.

-

備前国畠田守家Bizen no Kuni Hatakeda Moriie

-

但額銘有之初二代之内Tadashi gakumei kore ari sho-nidai no uchiBears a gakumei and is a work of the first or second generation.

-

刃長弍尺弍寸六分有之Hacho ni shaku ni sun roku bu ari koreThe blade length is 68.5 cm

-

昭和卅三年晩秋吉祥日谷脇氏嘱Showa misojisannen bannen kichijônichi Taniwaki shi no tanomuA lucky day in 1958, on request of Mr. Taniwaki

-

寒山志Kanzan ShirusuInscribed by Kanzan (Dr. Sato Kanzan)

Designated as jûyô-tôken at the 15th jûyô-shinsa held on February 10th 1967

katana, gaku-mei: Moriie (守家)

Ôsaka, Nakai Kôzô (中井孝三)

measurements: nagasa 68.8 cm, sori 2.2 cm, motohaba 3.0 cm, sakihaba 2.2 cm, kissaki-nagasa 3.1 cm, nakago-nagasa 18.5 cm, only very little nakago-sori

shape: shinogi-zukuri, iori-mune, rather deep koshizori, chû-kissaki

kitae: itame mixed with mokume, in addition ji-nie and chikei

hamon:chôji in ko-nie-deki that features a wide nioiguchi and that is mixed with ko-chôji, ko-ashi, yô, sunagashi, and kinsuji, the nioiguchi is overall a little subdued

bôshi: shallow midare-komi with a ko-maru-kaeri and hakikake

horimono: on both sides a bôhi that runs with kaki-nagashi into the tang

nakago: ô-suriage, ha-agari kurijiri, shallow katte-sagari yasurime, one mekugi-ana, the haki-omote side bears a “Moriie” gaki-mei at the tip of the tang

Explanation:

According to tradition, Moriie was a smith who lived in Hatakeda which was located close to the village of Osafune in Bizen province. There are no signatures known which bear the supplement “Hatakeda” but we know a dated blade from Bun’ei nine (文永, 1272) which is signed with “Osafune-jû.” The workmanship is similar to that of the contemporary Osafune grandmaster Mitsutada.

This blade is ô-suriage and bears a “Moriie” gakumei at the tip of the tang but which is corroborated by the workmanship and the excellent deki.

—————————————————————————–

備前國畠田守家

但額銘有之初二代之内

刃長貮尺貮寸六分有之

昭和丗三年晩秋吉祥日谷脇氏嘱

寒山誌

Bizen no Kuni Hatakeda Moriie

Tadashi gakumei kore ari sho-nidai no uchi

Hachô ni shaku ni sun roku bu kore ari

Shôwa sanjûsannen bannen kichijônichi Taniwaki shi no tanomu

Kanzan shirusu

Bizen no Kuni Hatakeda Moriie

Bears a gakumei and is either a work of the first or the second generation.

Blade length ~ 68.5 cm

Written by Kanzan on a lucky day in late fall of 1958 on request of Mr. Taniwaki.