Description

There is likely sword manufacture going back deep into time, but the most famous products of Chikuzen are from the school of Samonji. This nickname of Samonji comes from the habit of signing his swords with the single character Sa (左). The signature of Sa is itself thought to be a nickname, short for his given name Saemon Saburo. Samonji would sign the Sa character on the omote side of a tanto, and sometimes on the other side he’d write Chikushu ju (meaning: a resident of Chikushu). This is an interesting habit of his and somewhat unique to his school. On the two signed tachi that exist (please note: other reference books will say there is only one, this is outdated information), he signed all on one side. There are however oshigata remaining of swords now lost, destroyed or now suriage mumei where he signed on both sides similar to tanto. His style of signature is held to be very beautiful, similar to brushwork calligraphy and so very aesthetically pleasing. It is compared in the old book Kokon Mei Zukushi to Awataguchi Yoshimitsu, which was claimed to be the model for his style of signing.

Samonji lived in Hakata Okinohama of Chikuzen province and was a true giant in the craft of the Japanese sword, and this respect for him is shown in a further nickname of O-Sa, meaning The Great Sa. Today we use the names Sa, O-Sa and Samonji interchangeably which may be confusing to beginners.

Preceding Samonji in Chikuzen was his father Jitsua, grandfather Sairen, and great grandfather Ryosai who is considered now to be founder of this line. Nyusai is a contemporary of Sairen and is the other famous old Chikuzen smith, and possibly Samonji’s great uncle.

Samonji’s predecessors all worked in a traditional and somewhat rustic local style. It was neither flashy nor flamboyant but these smiths retained considerable skill and are ranked Jo-saku and Jo-jo saku for superior to greatly superior levels of craftsmanship. Jitsua worked at the end of the Kamakura period and Samonji has dated work that has been discovered through time starting around Karyaku (1326) though these older works no longer exist now.

The early works dating up until 1339 resemble work of his teacher and father Jitsua and are in the old Chikuzen style. Starting around 1340, something changes and his work quite quickly becomes infused with the Soshu den. His last dated work is only known from old oshigata and is 1347. It is fair to believe his work period beginning a few years before 1326 and extending a few years past 1347, making him a man of the late Kamakura and early Nanbokucho periods, probably concurrent with Go Yoshihiro, Shizu and coming a bit before Sadamune. His students’ dated work take precedence starting at 1350 so this would likely be the end point of his career. So we have Soshu works appearing from Samonji for only approximately a 10 year period of time, making them quite rare overall.

He went up to the east and became a pupil of Soshu Masamune, and it is said in various books that have been handed down from the Muromachi period that his technical skills exceeded those of his teacher. […] Denial of the story about the Masamune Mon is difficult…

Nihonto Koza

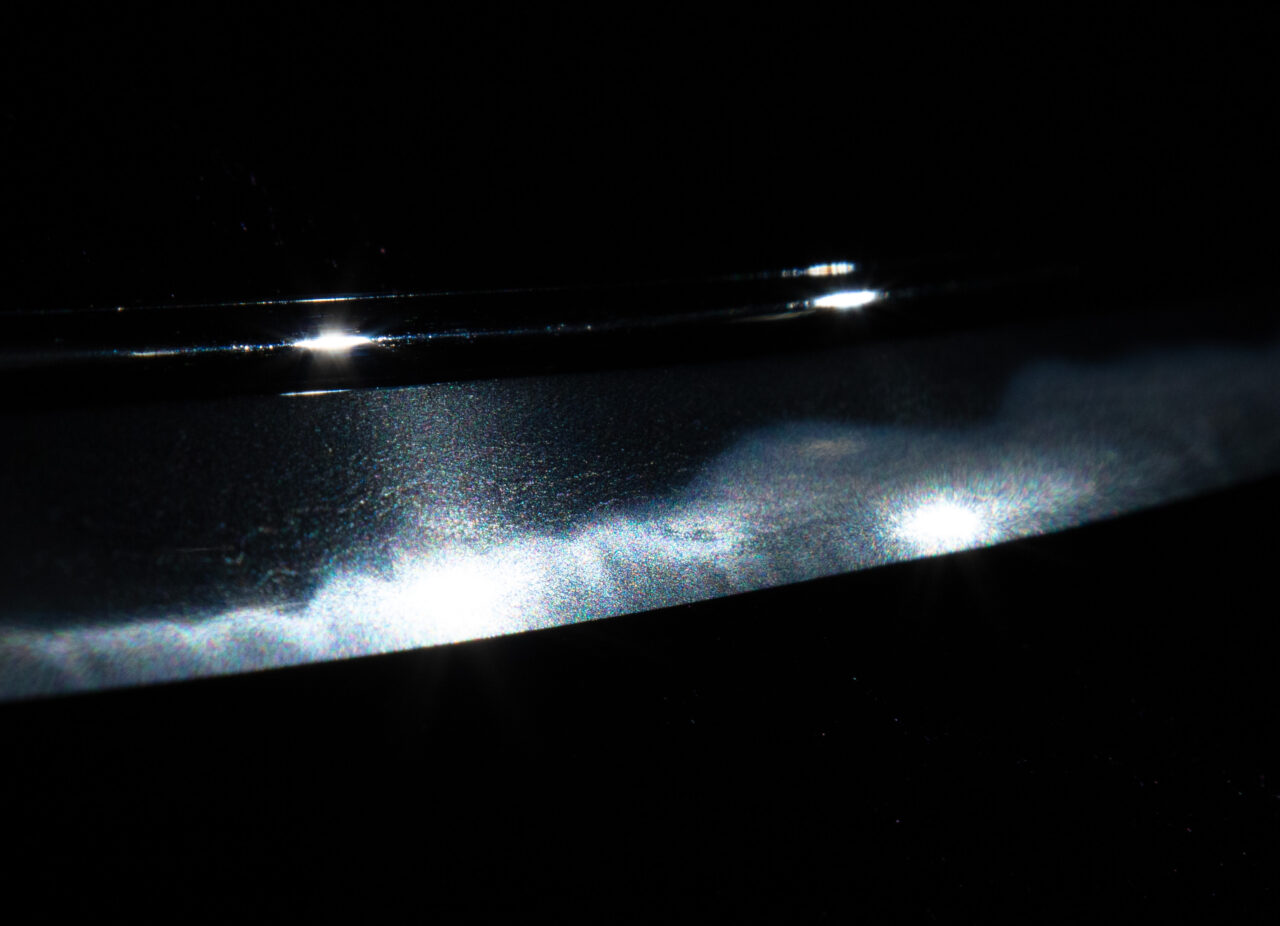

Samonji brought about a revolution in sword smithing in Chikuzen as his own style is the Soshu style founded in Kamakura by Shintogo Kunimitsu and perfected by Masamune, Yukimitsu and Norishige. In this his work features clear and beautiful steel with bright hamon, chikei and ji nie, which is not found among his predecessors. Because of this Samonji has since the Muromachi period been included in the Masamune no Juttetsu (10 great students of Masamune) in books like the Hidansho. Among these great smiths he is outranked only by Go Yoshihiro.

Sa is listed at the very top of the [Masamune no] Juttetsu and there is no one who can doubt this, as it is very much evident from the many works of Sa that we see today.

Albert Yamanaka, Nihonto Newsletters

Samonji’s work was highly sought after and considered very precious throughout history. For instance, Takeda Shingen requested a work of Samonji for his coming of age ceremony, and gave one to Oda Nobunaga’s son Nobutada. Oda Nobunaga when he killed Imagawa Yoshimoto, captured and took his tachi, the Yoshimoto Samonji tachi for himself, and sadly made it suriage, cutting it down from 78 cm to 65 cm. He had the Honami place a reference to his defeat of Yoshimoto in kinzogan on the new nakago. Like many other things made by Nobunaga, this sword eventually found its way into the hands of Tokugawa Ieyasu and handed down through the Shoguns. The Tokugawa in the Meiji period donated it to the Takeisao shrine which honors the spirit of Oda Nobunaga.

The Kosetsu Samonji tachi (which is one of only two surviving signed tachi by Samonji) was another famous tachi, this one owned by Toyotomi Hideyoshi before ending up with Tokugawa Ieyasu. The Kosetsu Samonji was handed down through the Shoguns and the Kishu Tokugawa branch of the family, and today is a National Treasure (Kokuho). As a side note he also has additional works at Kokuho, Juyo Bunkazai, and Juyo Bijutsuhin levels, which further indicates the reputation and regard in which this smith is held. That these blades are found with Nobunaga, Hideyoshi and Ieyasu, the three central warlords in the struggle to unify Japan illustrates the mystique surrounding Samonji in this time period.

Markus Sesko quotes one of the stories about Samonji and Masamune in one of his books:

A legend says that Samonji’s blades soon became sharper than those of his master which resulted in Masamune heading for an official post at the bakufu in order to expel Samonji from Kamakura. Well, Samonji returned to Sagami province and secretly forged from the outskirts of Kamakura, but as it was dangerous for him to be there without permission he left his blades unsigned.

Legends and Stories around the Japanese Sword

There is some modern argument about whether or not Samonji learned Soshu directly from Masamune, given the distance to Kamakura from Chikuzen. If we assume he did not, it leaves a gap where we need to explain the transmission from the grandmaster Masamune to some unknown smith to the grandmaster Samonji without any loss of skill or technique. If this were to happen then the unknown smith would be of equivalent level to his teacher Masamune and his student Samonji. The only credible alternative would be Sadamune but even so the same counter arguments apply. I don’t believe in leaving an empty gap in there for the Soshu teacher of Samonji. So, I agree with Yamanaka and accept the historical chronicle in this case, especially given the fact that Samonji very suddenly replaced the traditional Chikuzen style with Soshu den which we need otherwise believe happened out of nowhere.

This description certainly fits the description of Masamune in every detail. Many of the finer mumei tanto of Sa had been passed off As Masamune in the olden days. […] From the description we have made above, there is no reason to doubt that Sa was not a student of Masamune.

Albert Yamanaka, Nihonto Newsletters

The style of the two signed tachi by Samonji show work that retains the traditional Kamakura shape and predates the excessive sugata of the middle to late Nanbokucho period. These shapes we do see in the work of his students. His early tanto have very little to no sori and resemble Kamakura period tanto, and he is well regarded as a master craftsman of tanto, similar to Soshu Yukimitsu, Masamune, Norishige, Shintogo Kunimitsu and Sadamune. This is another strong element that ties Samonji to Masamune I believe, as this is something very distinctively associated with the Soshu den leading up to and including Sadamune. Like Sadamune, the later work of Samonji in tanto form changes and becomes slightly curved. Though, he does not seem to work as late as Sadamune as his tanto never grow to the larger middle Nanbokucho period styles. The largest Samonji tanto is only 27.4 cm and this one is almost 2 cm larger than the next, which is one of several that are around 25 cm long. This to me also places him in time as a little bit earlier than Sadamune and makes Masamune a more likely conduit to Samonji for the source of Soshu techniques.

Samonji himself was also a master teacher, with several great sons and students. The sons are Sa Yasuyoshi, Sa Yoshisada, Sa Yoshihiro. These sons were so talented that they have made swords that have reached Kokuho and Juyo Bunkazai levels. All of these smiths continued working in the Soshu style brought to Chikuzen by their teacher Samonji. The students are Sadayuki, Yukihiro and Sadayoshi. Fujishiro ranks Samonji at Sai-jo saku for highest level of skill, while all six of the sons and students and are also ranked very highly at Jo-jo saku. Together these six carried the Samonji school through the Nanbokucho and left many excellent students of their own in Chikuzen, Nagato and Hizen provinces. The line would diminish in the Muromachi period and finally any smiths of note conclude quietly with the Hirado Sa and Oishi Sa smiths in the 1500s.

It is a repeated habit of smiths in this line to occasionally sign only with the Sa character (左), so when encountering these works we must be particularly careful about attribution as it may be a reflex to consider them to be works of O-Sa himself. They are however fairly straight forward to separate based on period cues and technical ability as none of the descendants of the school were able to replicate the great skill of Samonji. Smiths who would come much later in the Horikawa school in early Shinto, all the way to the famous Kiyomaro in the Shinshinto period, took inspiration from and tried to copy the works of Samonji.

Probably due to their popularity, most works that are left of Samonji now are often tired from being polished so many times over the centuries. A major sword dealer in Japan was just recently mentioning to me how even in old books the condition of many Sa pieces were already compromised. Many of the tanto have been shortened, probably to retrofit them into high level mountings that were handed down in daimyo families. Even somewhat tired, signed Juyo tanto by Samonji can fetch very steep prices.

Healthy blades do not often appear on the market and are very much in the minority. Since there is only one signed tachi that is not Kokuho, it’s not possible to generalize on the price range of this category as the blade is entirely singular.

Lastly, during the Edo period a list was made of the most famous swords in the country. Almost 200 blades are in the list, 11 of which are Samonji, accounting for about 6% of the total. Today we can find Samonji blades in the collection of the Emperor of Japan. At the time of this writing, the NBTHK by my count has accepted 50 works of Samonji as Juyo and higher, so his work is quite difficult to come by. Of these 50, 18 are unsigned katana, one is a signed tachi, one is a tachi cut down to wakizashi, one is a naginata naoshi and 29 are tanto. Of those 50 blades, 10 katana, 1 tachi and 10 tanto went on to pass Tokubetsu Juyo. So this is almost half of the works of Sa going on to Tokuju that the NBTHK has assessed and indicates the high level of skill and regard in which the smith is held. There are an additional 9 Juyo Bijutsuhin, 6 Juyo Bunkazai and 3 Kokuho by Samonji, a very high number. Overall we are looking at only 68 examples remaining in existence by this smith, so we need to really understand by this how rare and precious they are especially given his great deal of fame.