Description

——————————————————————

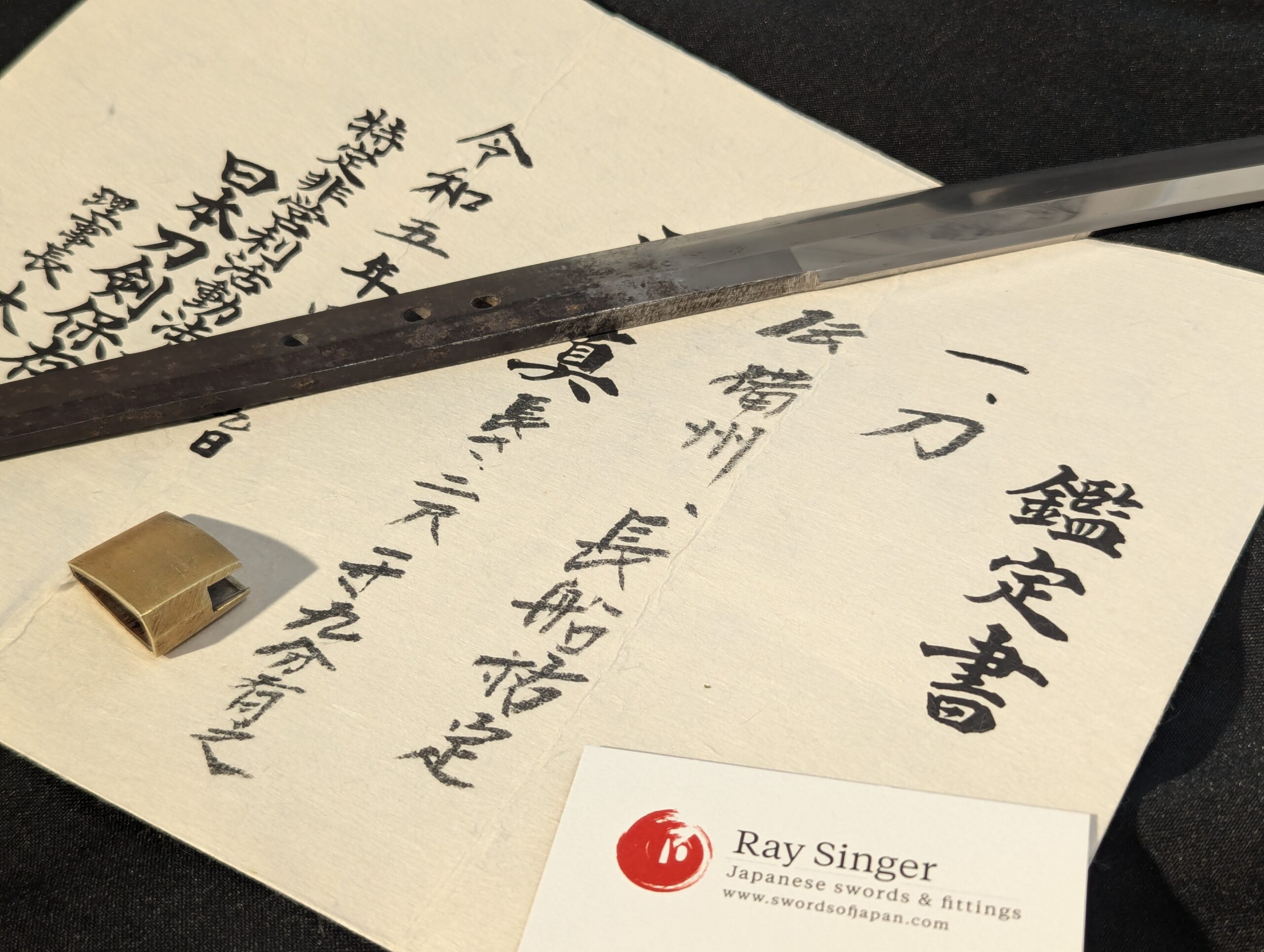

This is an excellent article on Sukesada by Darcy Brockbank, which was a setup for a description of a Yosozaemon Sukesada.

The setting is Japan, in Bizen province. The time-frame is near the end of the Muromachi period. The country has been at war for decades, and will be at war for decades to come. The great artistry of the past, which began to decline in the Nanbokucho period, was on a continuing downward spiral. The seemingly endless war had sapped finances and desires for artistic and showy weapons. Instead, the rule of the day was for simple, quickly made, and almost disposable utilitarian weapons. Groups of smiths were working as teams in a near assembly line effort to crank out cheap weapons quickly in order to meet demand. Thus, in the haste of producing swords cheaply, and quickly as the Muromachi period unfolded, the old skills that made the finest swords in the past were lost.

It was a time of fierce fighting, and gave birth to the one handed katate-uchi, a shorter version of the uchigatana from the previous age, it was worn edge up. For these, the drawing motion translates into a striking motion, and he who struck first with these sharp swords inevitably would win. It was a simple man’s sword for fighting on foot, worn thrust through the belt, and it along with the increased presence of naginata and yari on the fighting field sounded the death knell for the noble horse borne tachi. It was too large, too slow, too bulky, and so the tachi surrendered its place in history to what would develop into the katana.

However, even in this time of darkness there were bright lights. Kanemoto in Akasaka, Mino held a brilliant rivalry with his brother-by-choice Kanesada of Seki. Both made interesting and powerful blades, with Kanemoto developing the seeds of what would be a new hamon, the famous sanbonsugi that became synonymous with the line of smiths that would bear his name well into the future. Works of his hand often represent the highest degree of sharpness a sword can attain. Kanesada, perhaps more artistic, was able to grasp elements of the waning Soshu and Yamashiro traditions. Working in these styles as well as his native Mino, he made swords that remained beautiful and were also renowned for their sharpness. Of swords and smiths tested and ranked in the Kaiho Kenjaku (pub. 1797), and Kokon Kaji Biko (1830) , there are sixteen smiths granted the highest rating (Sai-jo O-wazamono: supreme sharpness). Kanesada and Kanemoto each belong to that elite club.

This is also the era of the very famous Muramasa in Ise. He is a smith cloaked in mystery and myth; a maker of famous swords, often considered evil, cursed and deadly to the owner as well as the target.

Standing above them all in skill was the best of the many Sukesada smiths, Yosozaemon no jo Sukesada in Bizen province. His father was Hikobei no jo Sukesada, a great smith in his own right, eclipsed as a Sukesada only by the skill of his son.

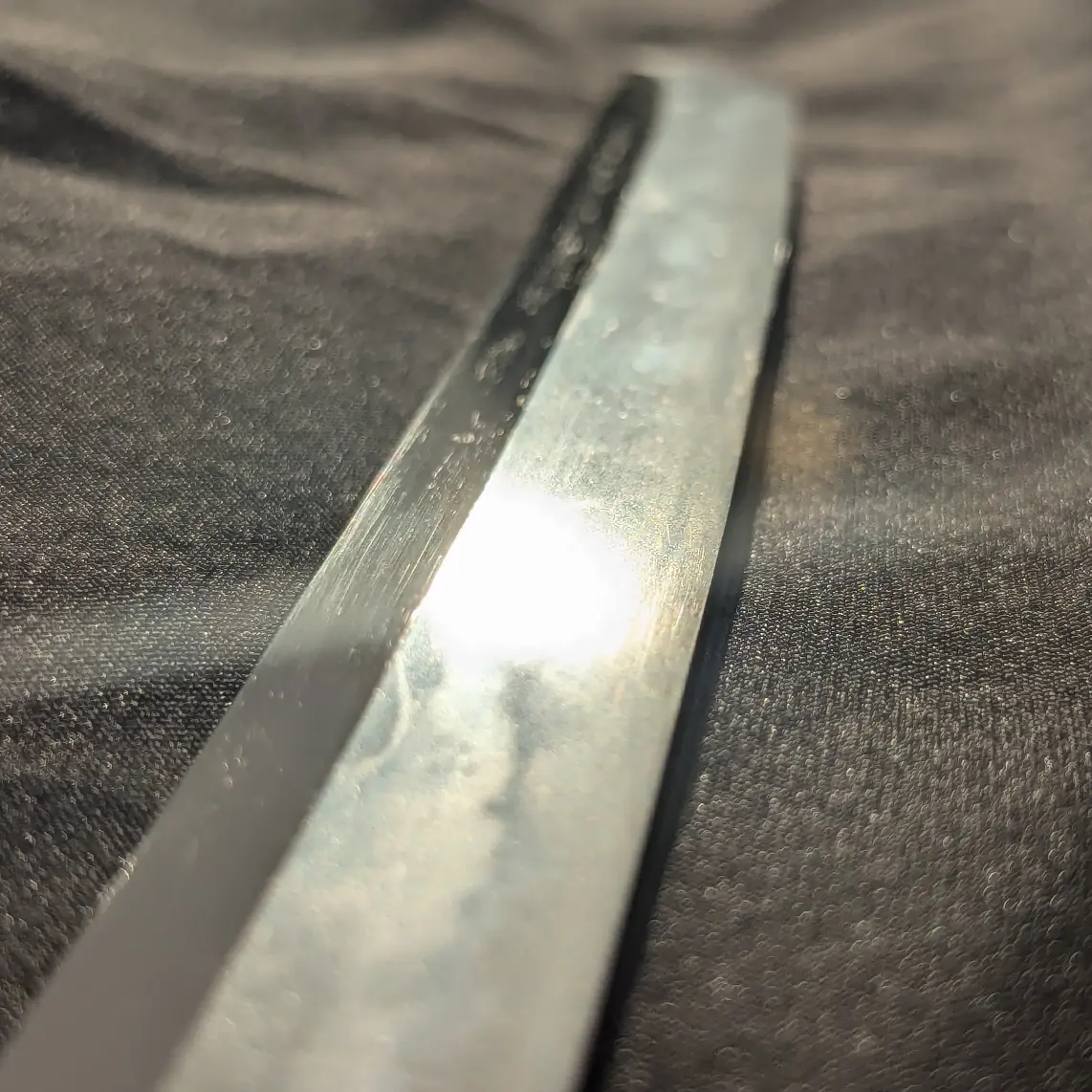

The craft of Yosozaemon was a throwback to earlier times; his is a unique artistry for the Muromachi period, and he stands as the last truly great Bizen smith before this tradition too fades into history. As such, he is considered the representative smith of his period and school, together commonly referred to as Sue Bizen.

Yosozaemon no jo Sukesada had two sons, the nidai Yosozaemon and Genbei no jo Sukesada, both smiths of excellent skill and workmanship. There is a daito in Japan signed both by Yosozaemon and Genbei, and is the only one of its kind that I am aware of. Swords like this are particularly important because they prove a chronology, a similar sword signed both by Hikobei and Yosozaemon names Yosozaemon as the son. Similarly this daito implies a teacher/student relationship at least, if not a filial one, between Yosozaemon and Genbei.

There exists a sword dated Tenmon Rokunen (1538) Nanaju Issai (age 71), and since Yosozaemon died at the age of 76, we know the date of his birth and death, 1467 and 1542 respectively. Yosozaemon continued making swords right until he died, encompassing 54 Juyo Token in his work, and is rated Sai-jo Saku by Fujishiro for greatest quality of workmanship, and O-wazamono for great sharpness. He is valued at 1,000 man yen in the Toko Taikan, but in practice, pieces by him do not often come onto the open market (especially daito).